Lesson 4: The Microeconomics of Development

ECON 317 · Economics of Development · Fall 2019

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/devf19

devF19.classes.ryansafner.com

The Micro -economics of Development

Economists try to model "an economy" in a way that:

- explains economic growth

- is exploitable for policymakers

Before we do that (can we?):

How does a market economy work? and grow?

Microeconomic foundations to answer Macroeconomic questions

- Micro: [modelling] Choices and consequences

- Macro: [modelling] Systemic interaction of choosers & emergent behavior (dis/coordination)

The Division of Labor

Self-Sufficiency...and Poverty

Complete Interdependence...and Unparalleled Prosperity

Interdependence I

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"In civilized society [man] stands at all times in need of the cooperation and assistance of great multitudes, while his whole life is scarce sufficient to gain the friendship of a few persons...man has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only," (Book I, Chapter 2.2).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

Interdependence II

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"Whoever offers to another a bargain of any kind, proposes to do this. Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want, …and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest," (Book I, Chapter 2.2).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

Interdependence III

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"[Though] he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention…By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it" (Book IV, Chapter 2.9).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

How to Get Rich or Die Tryin' I

- For 1,000s of years, the elite could become wealthy only by this...

How to Get Rich or Die Tryin' II

- But for the last 200 years, the average citizen can become wealthy by this...

The Division of Labor I

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which it is any where directed, or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labour," (Book I, Chapter 1).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

The Division of Labor II

Output performed under the division of labor exceeds output performed in isolation (autarky)

Variation in factor endowments

Variation in production opportunities

Variation in human talents

The Division of Labor III

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"It is but a very small part of a man's wants which the produce of his own labour can supply. He supplies the far greater part of them by exchanging that surplus part of the produce of his own labour, which is over and above his own consumption, for such parts of the produce of other men's labour as he has occasion for. Every man thus lives by exchanging, or becomes in some measure a merchant, and the society itself grows to be what is properly a commercial society," (Book I, Chapter 4).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

Smith's Pin Factory Example I

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"To take an example...from a very trifling manufacture...the trade of the pin-maker. [I]n the way in which this business is now carried on, not only the whole work is a peculiar trade, but it is divided into a number of branches, of which the greater part are likewise peculiar trades. One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head...and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations...Ten men only were employed [and they] could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day...But if they had all wrought separately and independently [they] certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day..." (Book I, Chapter 1).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

Smith's Pin Factory Example II

Adam Smith's pin factory illustration

Division of Labor: Origins

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"This division of labour, from which so many advantages are derived, is not originally the effect of any human wisdom, which foresees and intends that general opulence to which it gives occasion. It is the necessary, though very slow and gradual, consequence of a certain propensity in human nature which has in view no such extensive utility; the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another," (Book I, Chapter 2).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

The Division of Labor Is Limited By the Extent of the Market

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"As it is the power of exchanging that gives occasion to the division of labour, so the extent of this division must always be limited by...the extent of the market. When the market is very small, no person can have any encouragement to dedicate himself entirely to one employment, for want of the power to exchange all that surplus part of the produce of his own labour, which is over and above his own consumption, for such parts of the produce of other men's labour as he has occasion for," (Book I, Chapter 3).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

The Division of Labor: Summary

Division of labor: process where people specialize in production and then exchange their produce with others to acquire all of their desired goods

Two senses:

- Factory system: splitting up production process into specialized discrete steps boosts productivity

- Economic system: an economy of people specialize & exchange for all needs, leading to widespread prosperity

The more trading opportunities, the greater the benefits of specialization

The Division of Labor and Capital Accumulation I

Allyn Young

1876-1929

"The important thing, of course, is that with the division of labour a group of complex processes is transformed into a succession of simpler processes, some of which, at least, lend themselves to the use of machinery. In the use of machinery and the adoption of indirect processes there is a further division of labour, the economies of which are again limited by the extent of the market. It would be wasteful to make a hammer to drive a single nail; it would be better to use whatever awkward implement lies conveniently at hand," (p.530).

Young, Allyn, 1928, "Increasing Returns and Economics Progress," Economic Journal 38(152)

The Division of Labor and Capital Accumulation II

Allyn Young

1876-1929

"It would be wasteful to furnish a factory with an elaborate equipment of specially constructed jigs, gauges, lathes, drills, presses and conveyors to build a hundred automobiles; it would be better to rely mostly upon tools and machines of standard types, so as to make a relatively larger use of directly applied and a relatively smaller use of indirectly-applied labour. [Henry] Ford's methods would be absurdly uneconomical if his output were very small, and would be unprofitable even if his output were what many other manufacturers of automobiles would call large.," (p.530).

Young, Allyn, 1928, "Increasing Returns and Economics Progress," Economic Journal 38(152)

The Division of Labor and Capital Accumulation III

More trading opportunities create economies of scale

- As ↑ output, ↓ average cost

Makes large investments in capital & technology profitable

- Spreads fixed cost over a larger volume of sales

Labor-saving technologies

- May replace labor entirely with capital

- Might create new complex tasks for labor

The Division of Knowledge

- Greater extent of the market → greater division of labor, and also a greater specialization and division of knowledge

The Division of Knowledge

- Greater extent of the market → greater division of labor, and also a greater specialization and division of knowledge

From Subsistence to Exchange I

P. T. Bauer

1915-2002

"In emerging economies the activities of traders promote not only the more efficient deployment of available resources, but also the growth of resources. Trading activities are productive in both static and dynamic senses," (p.4)

"Instead, in spite of the economic history of the now-developed world, which should have been fa- miliar to development economists, trading activities are barely mentioned in the mainstream literature," (p.4)

Bauer, Peter, 2000, "From Subsistence to Exchange," in Bauer, P. T., From Subsistence to Exchange, and Other Essays, Princeton University Press

From Subsistence to Exchange II

P. T. Bauer

1915-2002

"Moreover, even a cursory reading of the last hundred years' history ... would have drawn attention to the role of traders in helping to transform them from largely subsistence economies to largely exchange economies," (p.5).

"These investments were made in the context of their decisions, encouraged by the activities of traders, to replace subsistence production by production for the market," (p.6)

Bauer, Peter, 2000, "From Subsistence to Exchange," in Bauer, P. T., From Subsistence to Exchange, and Other Essays, Princeton University Press

From Subsistence to Exchange III

P. T. Bauer

1915-2002

"Conditions in the Third World tend to ensure the need for a substantial volume of trading and closely related activities. These activities are more labor intensive than in the West because capital is scarcer relative to labor in poor countries than in rich. A large proportion of producers and consumers operate on a small scale and far from the major commercial centers, including the ports. Individual transactions are small. Individual farmers produce on a small scale and sell in even smaller quantities at frequent intervals because they lack stor- age facilities and substantial cash reserves. Conversely, because of their low incomes, consumers find it convenient or necessary to buy in small, often very small, amounts, again at frequent intervals." (pp.8-9)

Bauer, Peter, 2000, "From Subsistence to Exchange," in Bauer, P. T., From Subsistence to Exchange, and Other Essays, Princeton University Press

From Subsistence to Exchange III

P. T. Bauer

1915-2002

"To a Western audience it may seem as if sales of produce and purchases of consumer goods in such small quantities must be wasteful. This is not so...What may be somewhat surprising is that a large part of this labor is self-employed. This is so because entry into small-scale trading is easy...For these reasons small-scale operations are economic in many parts of the distribution system: large firms are at a disadvantage because their operations require more administrative and supervisory personnel, and these tend to be relatively expensive or ineffective in many poor countries. A multiplicity of small-scale traders in part represents the substitution of cheaper labor for more expensive labor," (p.9-10)

Bauer, Peter, 2000, "From Subsistence to Exchange," in Bauer, P. T., From Subsistence to Exchange, and Other Essays, Princeton University Press

From Subsistence to Exchange IV

P. T. Bauer

1915-2002

"Farmers in poor countries producing for wider exchange have to make in- vestments of various kinds. These investments include the clearing and im- provement of land and the acquisition of livestock and equipment. Such investments constitute capital formation. A part of this capital formation is financed from personal savings and borrowing from traders and others. But much of it is nonmonetized...These forms of investment, when made by small farmers, are generally omitted from official statistics and are still largely ignored in both the aca- demic and the official development literature. [But] these categories of investment are critical in the advance from subsistence to exchange." (pp.11-12)

Bauer, Peter, 2000, "From Subsistence to Exchange," in Bauer, P. T., From Subsistence to Exchange, and Other Essays, Princeton University Press

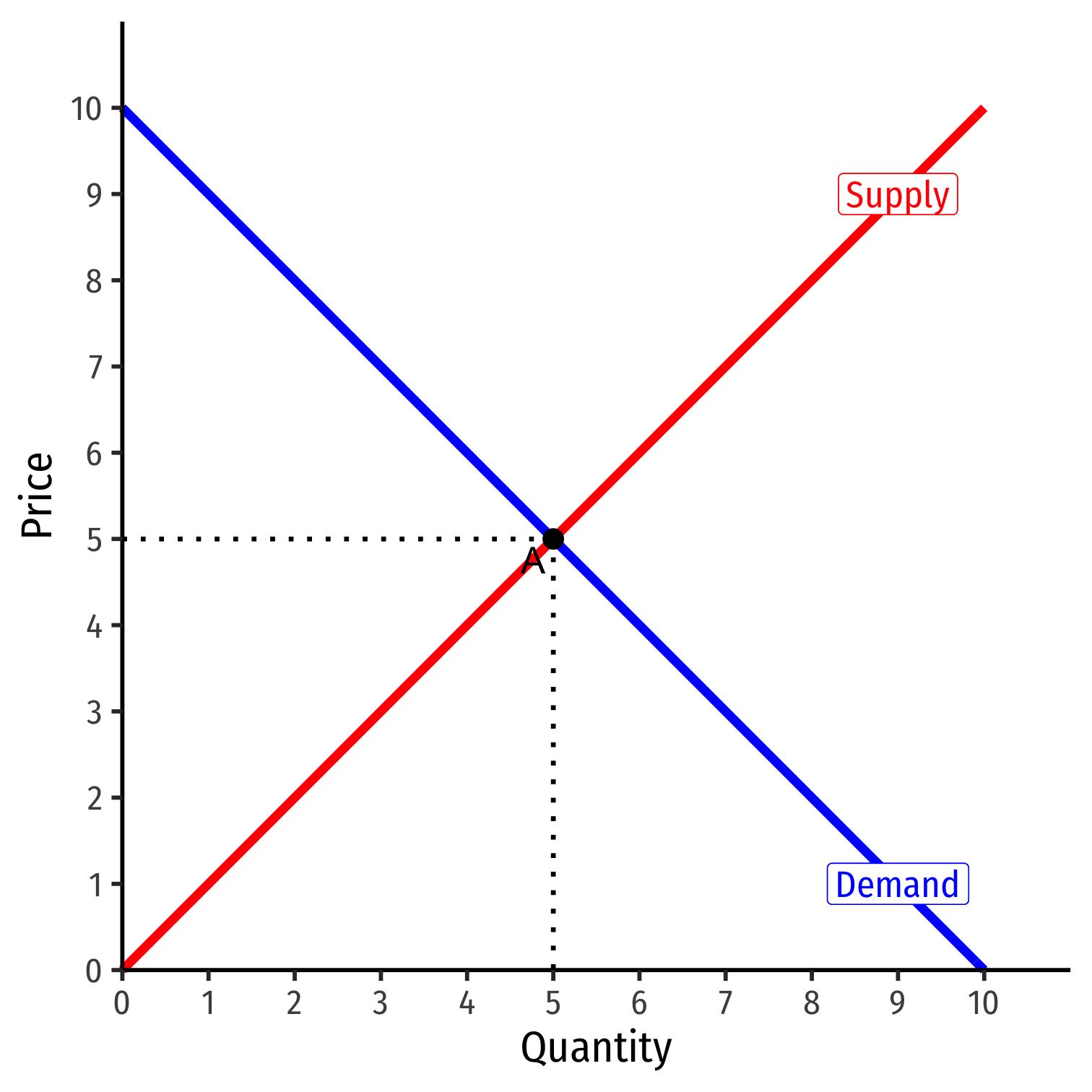

Why Markets Tend Towards an Equilibrium

The Law of One Price I

- Law of One Price: all identical goods will tend to have the same market price

The Law of One Price II

Consider if there are multiple different prices for same good:

Arbitrage opportunities: optimizing individuals recognize profit opportunity:

- Buy at low price, resell at high price!

- There are possible gains from trade or gains from innovation to be had

Entrepreneurship: recognizing profit opportunities and entering a market as a seller to try to capture gains from trade/innovation

Arbitrage and Entrepreneurship I

Arbitrage and Entrepreneurship II

Arbitrage and Entrepreneurship III

Entrepreneurship

Mark Zuckerberg

1984-

"Why were we the ones to build [Facebook]? We were just students. We had way fewer resources than big companies. If they had focused on this problem, they could have done it. The only answer I can think of is: we just cared more. While some doubted that connecting the world was actually important, we were building. While others doubted that this would be sustainable, we were forming lasting connections."

How Markets Get to Equilibrium I

Nobody knows "the right price" for things

Buyers and sellers only know their own reservation prices

Buyers and sellers adjust bids/asks

Markets do not start competitive, but monopolistic!

New entrepreneurs enter to try to capture gains from trade/innovation

As these gains are exhausted, prices converge to equilibrium

How Markets Get to Equilibrium II

Errors and imperfect information ⟹ multiple prices

- ⟹ arbitrage opportunities ⟹ entrepreneurship

- ⟹ correcting mistakes ⟹ people update their behavior & expectations

Markets are discovery processes that discover the right prices, the optimal uses of resources, and cheapest production methods, none of which can be known in advance!

How Markets Get to Equilibrium III

Consider the economy as a cat-and-mouse game between two sets of variables:

- "Underlying variables": preferences, technology, and resource availability

- "Induced variables": market prices, least-cost technologies

Induced variables always chasing underlying variables

- Underlying variables always changing

- Any time underlying and induced variables are different, profit opportunities

IF underlying variables froze, market would rest at equilibrium

When and Why Markets are Great

The Origins of Exchange I

Why do we trade?

Resources are in the wrong place!

People have better uses of resources than they are currently being used!

The Origins of Exchange II

Why are resources in the wrong place?

We have the same stuff but different preferences

The Origins of Exchange III

Why are resources in the wrong place?

We have the same stuff and/but different preferences

Transaction Costs and Exchange I

- But Transaction costs!

- Search costs: cost of finding trading partners

- Bargaining costs: cost of reaching an agreement

- Enforcement costs: trust between parties, cost of upholding agreement, dealing with unforeseen contingencies, punishing defection, using police and courts

Transaction Costs and Exchange II

With high transaction costs, resources cannot be traded

Resources cannot be switched to higher-valued uses

If others value goods higher than their current owners, resources are inefficiently allocated!

Transaction Costs and Exchange III

Markets are institutions that facilitate voluntary impersonal exchange and reduce transaction costs

There's a lot of institutions in the "bundle" we call "markets":

- Prices, profits and losses, property rights, rule of law, contract enforcement, dispute resolution, protection, trust

All of these things are assumed when we draw nice supply & demand graphs on the blackboard

- Much of this course: how do various political institutions enable these market institutions?

Social Problems that Markets Solve Well

Problem 1: Resources have multiple uses and are rivalrous

Problem 2: Different people have different subjective valuations for uses of resources

It is inefficient (immoral?) to use a resource in a way that prevents someone else who values it more from using it!

Social Problems that Markets Solve Well

Problem 1: Resources have multiple uses that are rivalrous

Problem 2: Different people have different subjective valuations for uses of resources

It is inefficient (immoral?) to use a resource in a way that prevents someone else who values it more from using it!

Solution: Prices in a functioning market accurately measure opportunity cost of using resources in a particular way

- The price of a resource is the amount someone else is willing to pay to acquire it from its current use/owner

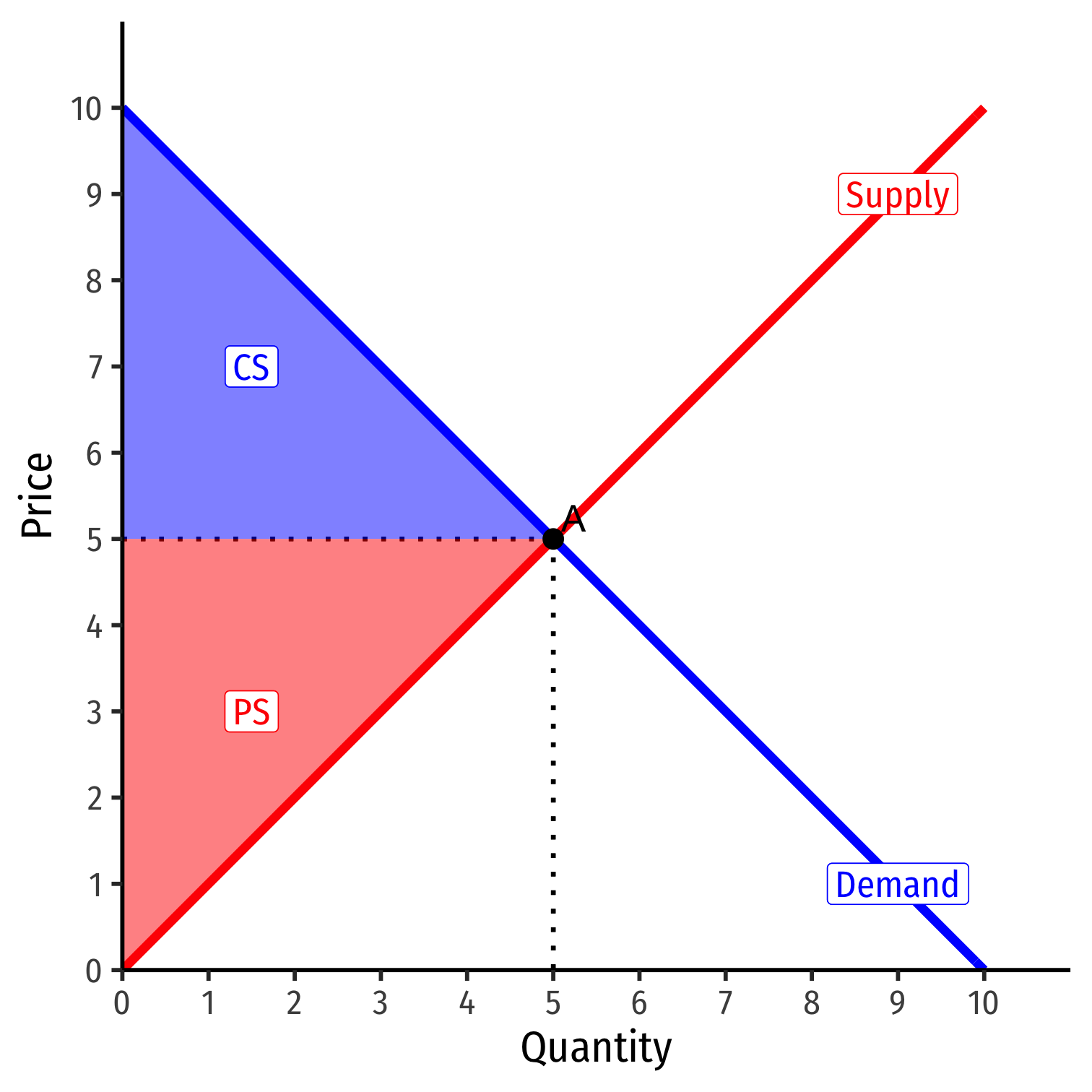

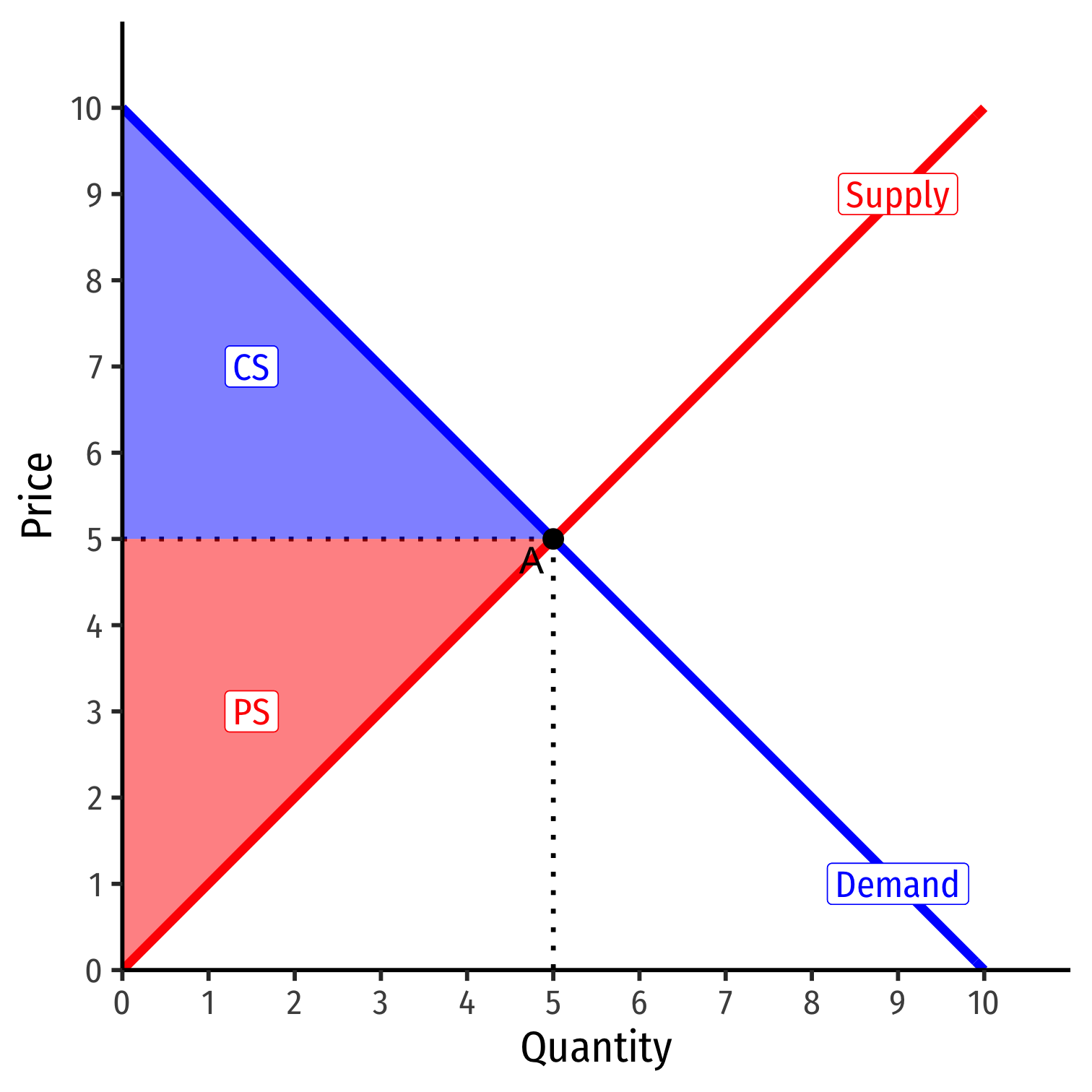

Markets and Pareto Efficiency

Voluntary exchange is a Pareto improvement: change in allocation that makes at least one person better off and making nobody worse off

An allocation of resources is Pareto efficient when there are no possible Pareto improvements

Markets and Pareto Efficiency

Pareto efficiency is conceptual gold standard: allow all welfare-improving exchanges so long as nobody gets harmed

In practice: Pareto efficiency is a first best solution

- only takes one holdout to disapprove to violate Pareto

Markets and Kaldor-Hicks Efficiency

Kaldor-Hicks Improvement: an action improves efficiency its generates more social gains than losses

- those made better off could in principle compensate those made worse off

Kaldor-Hicks efficiency: no potential Kaldor-Hicks improvements exist

Keeps intuitive appeal of Pareto but more practical

- Every Pareto improvement is a KH-improvement (but not the other way around!)

Consider policies where winners' maximum WTP > losers' minimum WTA

Policies should maximize social value of resources

Market Efficiency in Competitive Equilibrium I

Allocative efficiency: resources are allocated to highest-valued uses

- Goods produced up to the point where MB=MC (p=MC)

Pareto efficient: no possible Pareto improvements exist

All potential gains from trade are fully exhausted

Market Efficiency in Competitive Equilibrium II

Economic surplus = Consumer surplus + Producer surplus

Maximized in competitive equilibrium

Resources flow away from those who value them the lowest to those that value them the highest

Welfare Economics

The 1st Fundamental Welfare Theorem: markets in competitive equilibrium maximize allocative efficiency of resources and are Pareto efficient

Markets are great when they:

Are Competitive: many buyers and many sellers

Reach equilibrium: absence of transactions costs or policies preventing prices from adjusting to meet supply and demand

No externalities are present: costs and benefits are fully internalized by the parties to transactions

- If any of these conditions are not met, we have market failure

- May be a role for government, other institutions, or entrepreneurs to fix

The Social Functions of Market Prices

Aside: Returning to the Socialist Calculation Debate

Neoclassical economists and market socialists (Lange, Lerner, Bergson, etc) disagree with nothing so far

Argued that central planning can replicate the optimal outcomes of markets in competitive equilibrium without the problems

- Externalities

- Monopolies

- Inequality

- Unemployment

- Business cycles

The Neoclassical/Socialist View of Prices I

Prices as sufficient statistics in static equilibrium

Efficiency of prices: function in equilibrium market-clearing & achieving Pareto optimality

When prices changes, they don't lose their parametric function, and every individual always takes "the price" as given (price-taking behavior)

The Neoclassical/Socialist View of Prices II

Competition: an optimal end-state:

- Consumers maximized utility

- Producers minimized cost

- Economic profits are zero

- No surpluses or shortages

If you find the right vector of prices, given consumer preferences and given production functions, you can calculate this optimal outcome!

Hayek's Realization From Mises

Competition is not an optimal end-state, it is a discovery process!

Competition is not a noun, it's a verb!

Hayek: Markets as a Discovery Process I

F. A. Hayek

1899-1992

Economics Nobel 1974

"Planning in the specific sense in which the term is used in contemporary controversy necessarily means central planning - direction of the whole economic system according to one unified plan. Competition, on the other hand, means decentralized planning by many separate persons," (pp.519-520).

Hayek, F. A., 1945, "The Use of Knowledge in Society," American Economic Review 35(4): 519-530

Hayek: Markets as a Discovery Process II

F. A. Hayek

1899-1992

Economics Nobel 1974

"The economic problem of society is thus not merely a problem of how to allocate given resources if given is taken to mean given to a single mind which deliberately solves the problem set by these data. It is rather a problem of how to secure the best use of resources known to any of the members of society, for ends whose relative importance only these individuals know. Or, to put it briefly, it is a problem of the utilization of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality," (pp.519-520).

Hayek, F. A., 1945, "The Use of Knowledge in Society," American Economic Review 35(4): 519-530

Hayek: Markets as a Discovery Process III

F. A. Hayek

1899-1992

Economics Nobel 1974

"Which of the systems is likely to be more efficient...depends on whether we are more likely to succeed in putting at the disposal of a single central authority all the knowledge which ought to be used but which is initially dispersed among many different individuals, or in conveying to the individuals such additional knowledge as they need in order to enable them to fit their plans with those of others," (pp.519-520).

Hayek, F. A., 1945, "The Use of Knowledge in Society," American Economic Review 35(4): 519-530

Hayek: Markets as a Discovery Process IV

F. A. Hayek

1899-1992

Economics Nobel 1974

"The marvel is that in a case like that of a scarcity of a raw material, without an order being issued, without more than perhaps a handful of people knowing the cause, tens of thousands of people whose identity could not be ascertained by months of investigation, are made to use the material or its products more sparingly," (pp.527).

Hayek, F. A., 1945, "The Use of Knowledge in Society," American Economic Review 35(4): 519-530

Hayek: Markets as a Discovery Process IV

F. A. Hayek

1899-1992

Economics Nobel 1974

"The problem arises because one of the most important forces which in a truly competitive economy brings about the reduction of costs to the minimum discoverable will be absent, namely, price competition...[T]he question is frequently treated as if the cost curves were objectively given facts. What is forgotten is that the method which under given conditions is the cheapest is a thing which has to be discovered, and to be discovered anew, sometimes almost from day to day, by the entrepreneur, and that, in spite of the strong inducement, it is by no means regularly the established entrepreneur, the man in charge of the existing plant, who will discover what is the best method," (p.196).

Hayek, F. A., 1948, "Socialist Calculation II: The Competitive Solution," Individualism and Economic Order

Hayek: Markets as a Discovery Process V

F. A. Hayek

1899-1992

Economics Nobel 1974

"The force which in a competitive society brings about the reduction of price to the lowest cost...is the opportunity for anybody who knows a cheaper method to come in at his own risk and to attract customers by underbidding the existing producers. But, if prices are fixed by the authority, this method is excluded," (p.196).

Hayek, F. A., 1948, "Socialist Calculation II: The Competitive Solution," Individualism and Economic Order

Mises-Hayek View of Prices

Prices are knowledge surrogates in dynamic disequilibrium

Efficiency of prices: use distributed knowledge and incentivize local actors to exploit opportunities, which reduce error and bring about greater social coordination

Prices are never "given", prices emerge dynamically from negotiation and market decisions of entrepreneurs and consumers

Competition: is a discovery process which discovers what consumer preferences are and what technologies are lowest cost, and how to allocate resources accordingly

The Social Functions of Prices I

A relatively high price

Information conveyed: good is relatively scarce

Incentivizes:

- Buyers: conserve use of this good, seek substitites

- Sellers: produce more of this good

- Entrepreneurs: find substitutes and innovations to satisfy this unmet need

The Social Functions of Prices II

A relatively low price

Information conveyed: good is relatively abundant

Incentivizes:

- Buyers: substitute away from expensive goods towards this good

- Sellers: Produce less of this good, talents better served elsewhere

- Entrepreneurs: talents better served elsewhere: find more severe unmet needs

The Social Functions of Prices III

F. A. Hayek

1899-1992

Economics Nobel 1974

"The most significant fact about this system is the economy of knowledge with which it operates...by a kind of symbol [the price], only the most essential information is passed on and passed on only to those concerned...The marvel is that in a case like that of a scarcity of a raw material, without an order being issued, without more than perhaps a handful of people knowing the cause, tens of thousands of people whose identity could not be ascertained by months of investigation, are made to use the material or its products more sparingly," (p.527).

Hayek, F. A., 1945, "The Use of Knowledge in Society," American Economic Review 35(4): 519-530

Scientific vs. Tacit Knowledge I

F. A. Hayek

1899-1992

Economics Nobel 1974

"Today it is almost heresy to suggest that scientific knowledge is not the sum of all knowledge. But a little reflection will show that there is beyond question a body of very important but unorganized knowledge which cannot possibly be called scientific in the sense of knowledge of general rules: the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place. It is with respect to this that practically every individual has some advantage over all others in that he possesses unique information of which beneficial use might be made, but of which use can be made only if the decisions depending on it are left to him or are made with his active cooperation," (pp.521-522).

Hayek, F. A., 1945, "The Use of Knowledge in Society," American Economic Review 35(4): 519-530