Lesson 8: Introduction to Political Economy

ECON 317 · Economics of Development · Fall 2019

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/devf19

devF19.classes.ryansafner.com

Institutions and Political Economy

ECON 101 Makes a Lot of Assumptions About Institutions

Markets & price theory: how consumers and producers specialize, produce, and exchange within given, well-functioning markets (and politics)

Assumes the existence of "good" economic and political institutions that facilitate market exchange

- clear and enforced property rights (to goods, land, investment, ideas, etc)

- rule of law

- contract enforcement

- dispute resolution

- complete contracts

- low or no transaction costs

- high level of social trust

- capable, high-capacity, non-corrupt government

Perhaps the Opposite Extreme is More Realistic

Raguram Rajan

1963-

"And there is hope, supported by a growing body of research, that more students of development are realizing that a better starting point for analysis than a world with only minor blemishes may be a world where nothing is enforceable, property and individual rights are totally insecure, and the enforcement apparatus for every contract must be derived from first principles - as in the world that Hobbes so vividly depicted. Not only will this kind of work more closely approximate reality in the poorest, conflict-ridden countries, but it could also lead to more sensible policy", (p.56).

Rajan, Raghuram, 2004, "Assume Anarchy?," Finance and Development September: 56-57

"New Institutional Economics"

"New Institutional Economics" (1970s-): focus on the importance of institutions, economic history, transactions costs, and economic organization in understanding economics

|

|

|

|

| Ronald Coase | Douglass North | Elinor Ostrom | Oliver Williamson |

| 1910-2013 | 1920-2015 | 1933-2012 | 1932- |

| Economics Nobel 1991 | Economics Nobel 1993 | Economics Nobel 2009 | Economics Nobel 2009 |

Recall: Two Fundamental Problems of Political Economy

- All societies face two fundamental problems, which institutions emerge (or are created) to address:

The Knowledge Problem: How to coordinate the tacit, fragmented knowledge of opportunities and conditions dispersed across millions of individuals (and accessible to none in total) in order to maximize the ability of individuals to achieve their goals

Recall: Two Fundamental Problems of Political Economy

- All societies face two fundamental problems, which institutions emerge (or are created) to address:

The Knowledge Problem: How to coordinate the tacit, fragmented knowledge of opportunities and conditions dispersed across millions of individuals (and accessible to none in total) in order to maximize the ability of individuals to achieve their goals

The Incentives Problem: How to structure incentives that individuals face in a way that maximizes cooperative behavior (voluntary exchange and association) and minimizes non-cooperative behavior (cheating, opportunism, exploitation, violence, rent-seeking)

Recall: Making Fair Comparisons: Robust Political Economy I

- No system is perfect

We need to find arrangements that are robust to knowledge & incentive problems

Easy case: perfect information benevolence

Hard case: uncertainty and selfish behavior

Treat people as they are: sometimes good, bad, smart, stupid, opportunistic, altruistic depending on the institutions

Recall: Making Fair Comparisons: Robust Political Economy III

Recall: Making Fair Comparisons: Robust Political Economy IV

Economists often recommend optimal policies that could be installed by a benevolent despot

- A dispassionate ruler with total control, perfect information, and right incentives to implement optimal policy

- A "1st-best solution"

In reality, 1st-best policies are distorted by the knowledge problem, the incentives problem, and politics

- Real world: 2nd-to-nth-best outcomes

Recall: Comparative Analysis

Compare imperfections of feasible and relevant alternative systems

- Don't compare problems of an imperfect system with some ideal system!

Economics: think on the margin!

- One system's "failure" does not imply another's "success"!

- the real world requires tradeoffs

- "economics puts parameters on people's utopias"

- "compared to what?"

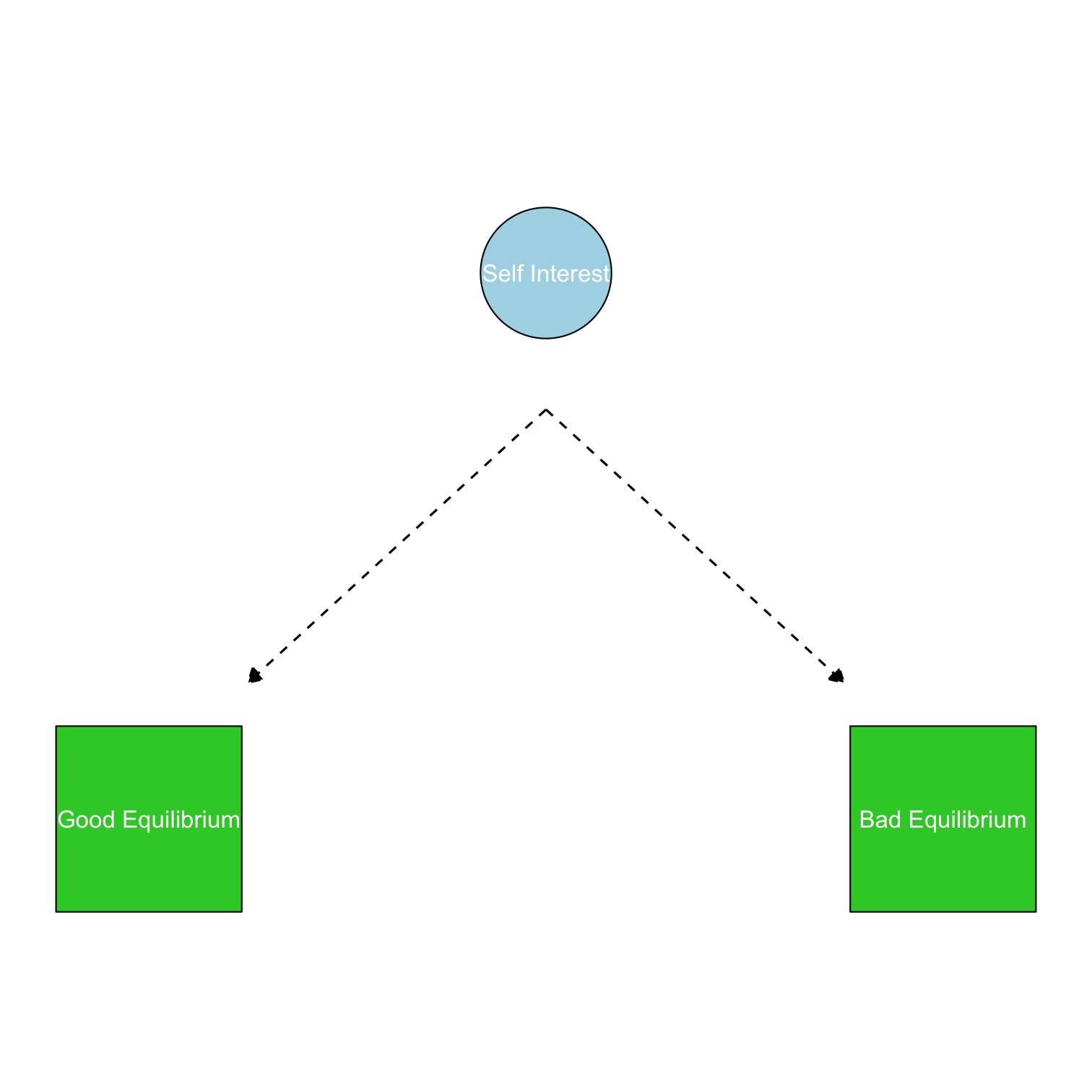

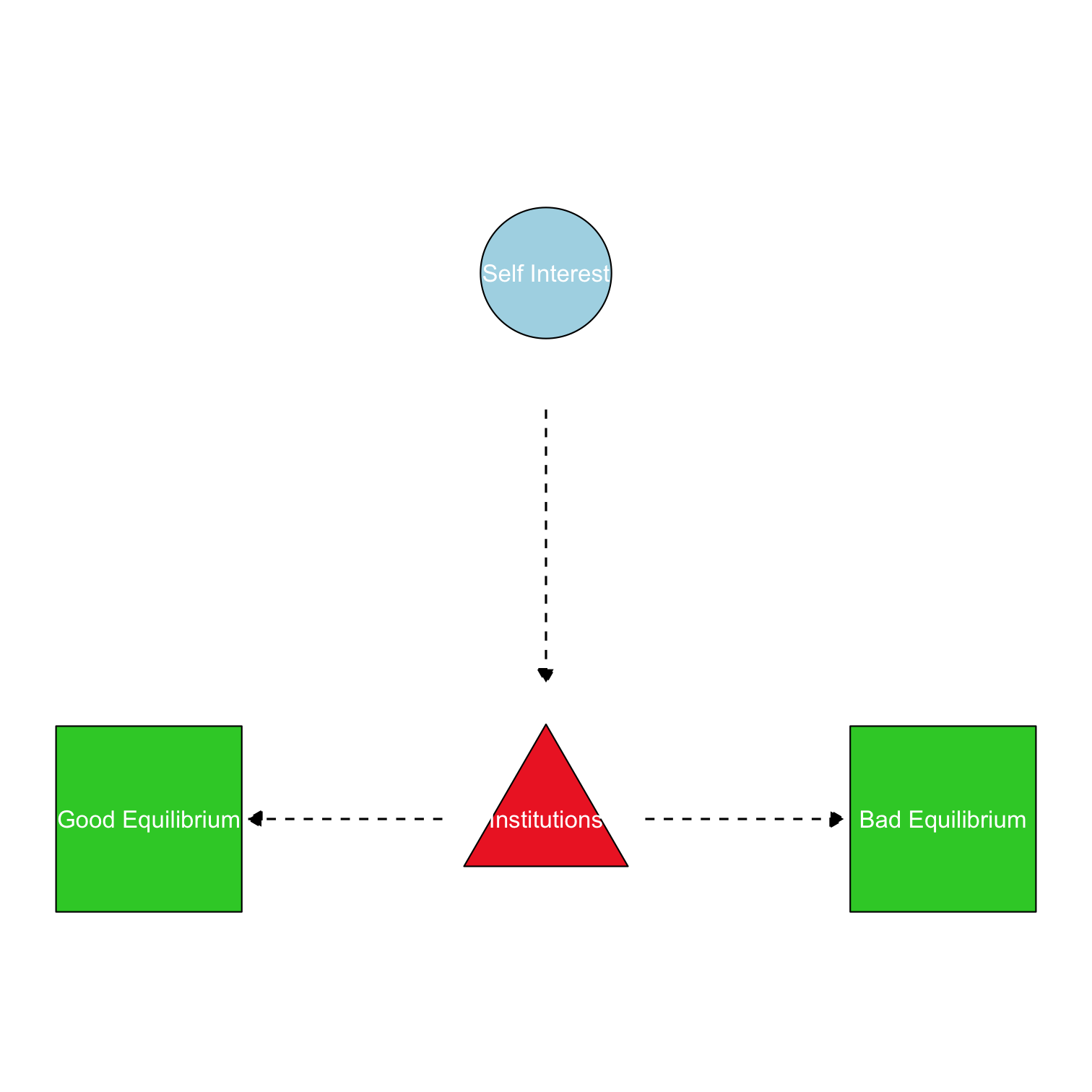

Institutions: Operationalizing Adam Smith

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"[Though] he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention…By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it," (Book IV, Chapter 2.9).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

Institutions: Operationalizing Adam Smith

"[Though] he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention…By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it," (Book IV, Chapter 2.9).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

Institutions: Operationalizing Adam Smith

"[Though] he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention…By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it," (Book IV, Chapter 2.9).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

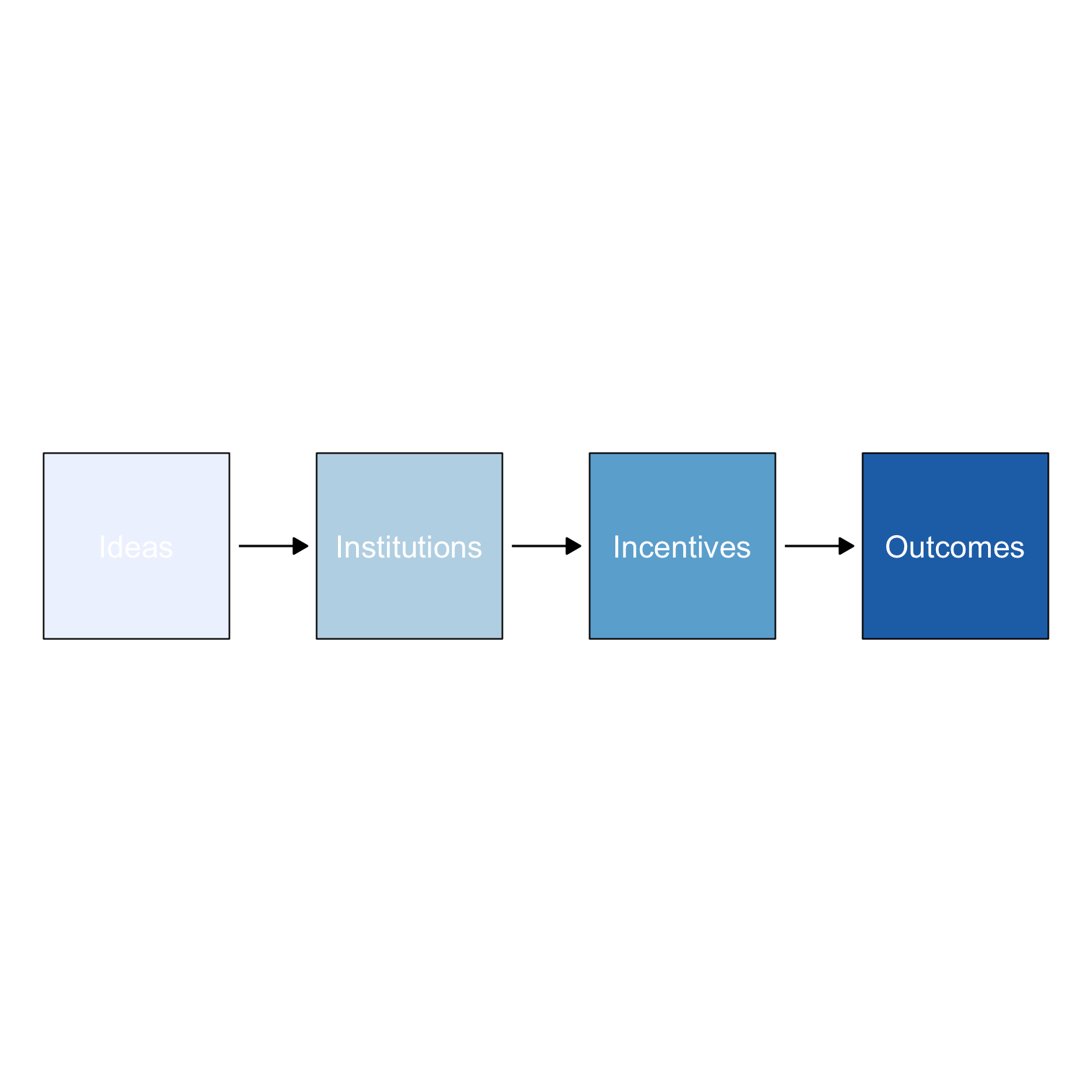

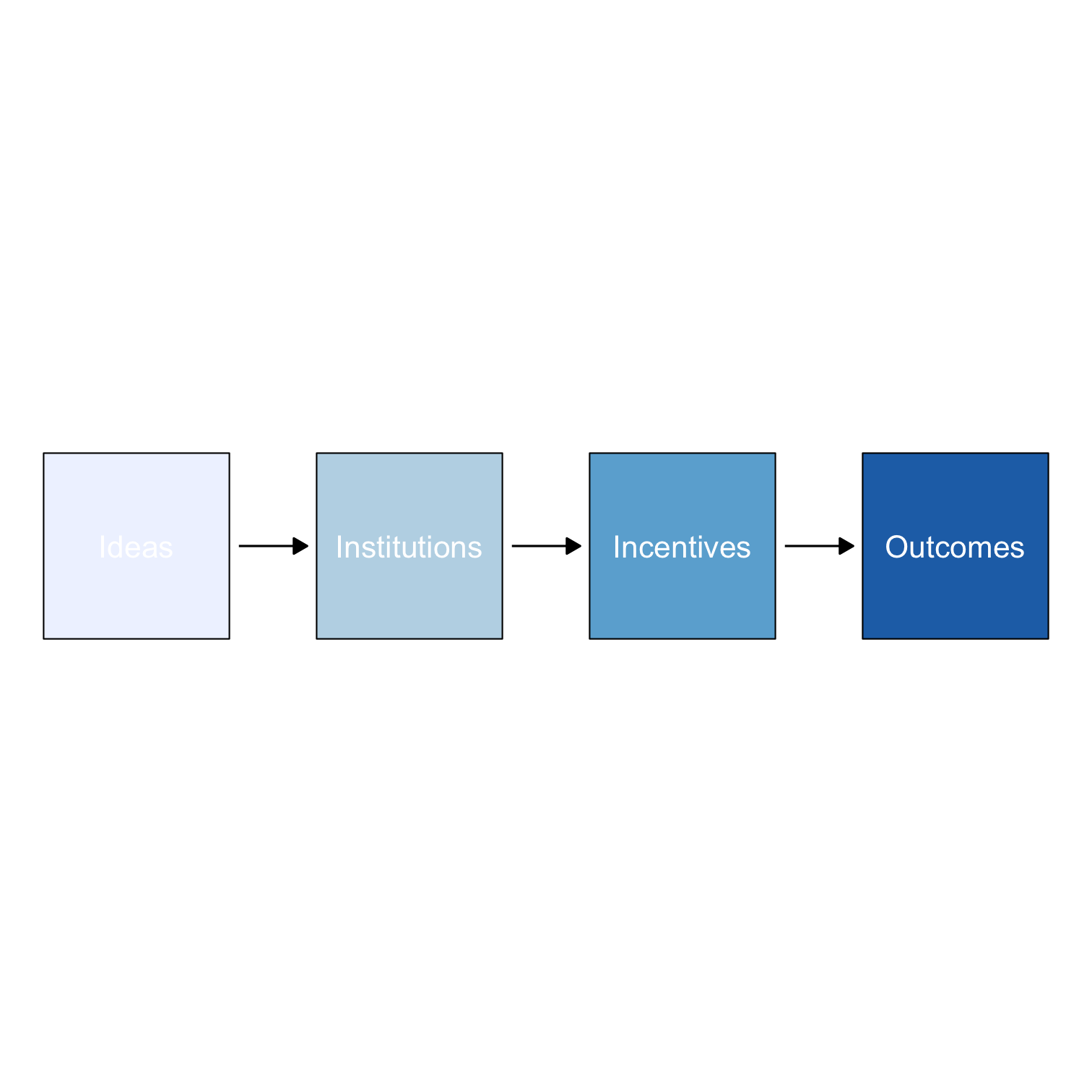

A Logical Framework for Political Economy

- Outcomes:

- relative level of wealth or poverty

- relative level of equality or inequality

- stability of politics, finance, macroeconomy

A Logical Framework for Political Economy

- Outcomes:

- relative level of wealth or poverty

- relative level of equality or inequality

- stability of politics, finance, macroeconomy

- ...are determined by Incentives:

- relative prices or costs of various choices

- profits and losses

- information

A Logical Framework for Political Economy

- Outcomes:

- relative level of wealth or poverty

- relative level of equality or inequality

- stability of politics, finance, macroeconomy

- ...are determined by Incentives:

- relative prices or costs of various choices

- profits and losses

- information

- ...are determined by Institutions:

- allocation of property rights, wealth, and power

- (in)equality before the law or corruption

- constraints on politics and economics

A Logical Framework for Political Economy

- Outcomes:

- relative level of wealth or poverty

- relative level of equality or inequality

- stability of politics, finance, macroeconomy

- ...are determined by Incentives:

- relative prices or costs of various choices

- profits and losses

- information

- ...are determined by Institutions:

- allocation of property rights, wealth, and power

- (in)equality before the law or corruption

- constraints on politics and economics

- ...are determined by Ideas:

- political and social worldview -"isms"

- which groups (should) have status

- moral and social norms

What are Institutions?

Douglass C. North

1920-2015

Economics Nobel 1993

"Institutions are the humanly devised constraints that structure political economic and social interaction. They consist of both informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights)", (p.10)

"Institutions are the rules of the game in a society", (p.1).

North, Douglass C, (1991), "Institutions," Journal of Economic Perspectives 5(1): 97-112.

North, Douglass C, (1990), Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance

Incentives are Structured by Institutions

"Who needs this nail?"

"Don't worry about it! The main thing is that we immediately fulfilled the plan for nails!

Markets are Disruptive: Creative Destruction

Markets as an Evolutionary Process

Joseph Schumpeter

1883-1950

"Capitalism...is by nature a form of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary...The essential point to grasp is that in dealing with capitalism we are dealing with an evolutionary process.," (pp.82).

"[I]n capitalist reality as distinguished from its textbook picture, it is not that kind of competition which counts but the competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization...competition which commands a decisive cost or quality advantage which strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives." (p.132).

Schumpeter, Joseph A, (1947), Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy

Creative Destruction I

Joseph Schumpeter

1883-1950

"Industrial mutation--if I may use that biological term—that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in" (p.83).

Schumpeter, Joseph A, (1947), Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy

Creative Destruction: Examples

Creative Destruction: Example II

Creative Destruction: Example III

59 years of progress

No Corporate Monolith Lasts Forever

Creative Destruction: The Problem

Creative Destruction: The Problem

Creative Destruction: The Problem

Creative Destruction: The Problem

Successful Economies Create a Political Problem I

Markets serve consumers (consumer sovereignty), not workers or producers!

Successful market economies produce wealth and destroy jobs

Economic growth ≡ more output with fewer inputs!

A political problem: how do producers permit the destructive side of creative destruction?

Successful Economies Create a Political Problem I

- Moral dilemmas:

- Do we have a moral obligation to insulate workers from the pain of competition that is no fault of their own?

- How do we secure the gains from trade and innovation without punishing the workers who lose their jobs?

Profit-Seeking and Rent-Seeking

Recall: Profit-Seeking

π=pq⏟revenues−(wl+rk)⏟costs

The firm's costs are all of the factor-owner's incomes!

- Landowners, laborers, creditors are all paid rent, wages, and interest, respectively

Profits are the residual value leftover after paying all factors

Profits are income for the residual claimant(s) of the production process (i.e. owner(s) of a firm):

- Entrepreneurs

- Shareholders

Recall: Who Gets the Profits?

π=pq⏟revenues−(wl+rk)⏟costs

Residual claimants have incentives to maximize firm's profits, as this maximizes their own income

Entrepreneurs and shareholders are the only participants in production that are not guaranteed an income!

- Starting and owning a firm is inherently risky!

Profits and Entrepreneurship

In markets, production must face the profit test:

- Is consumer's willingness to pay > opportunity cost of inputs?

Profits are an indication that value is being created for society

Losses are an indication that value is being destroyed for society

Survival for sellers in markets requires firms continually create value and earn profits or die

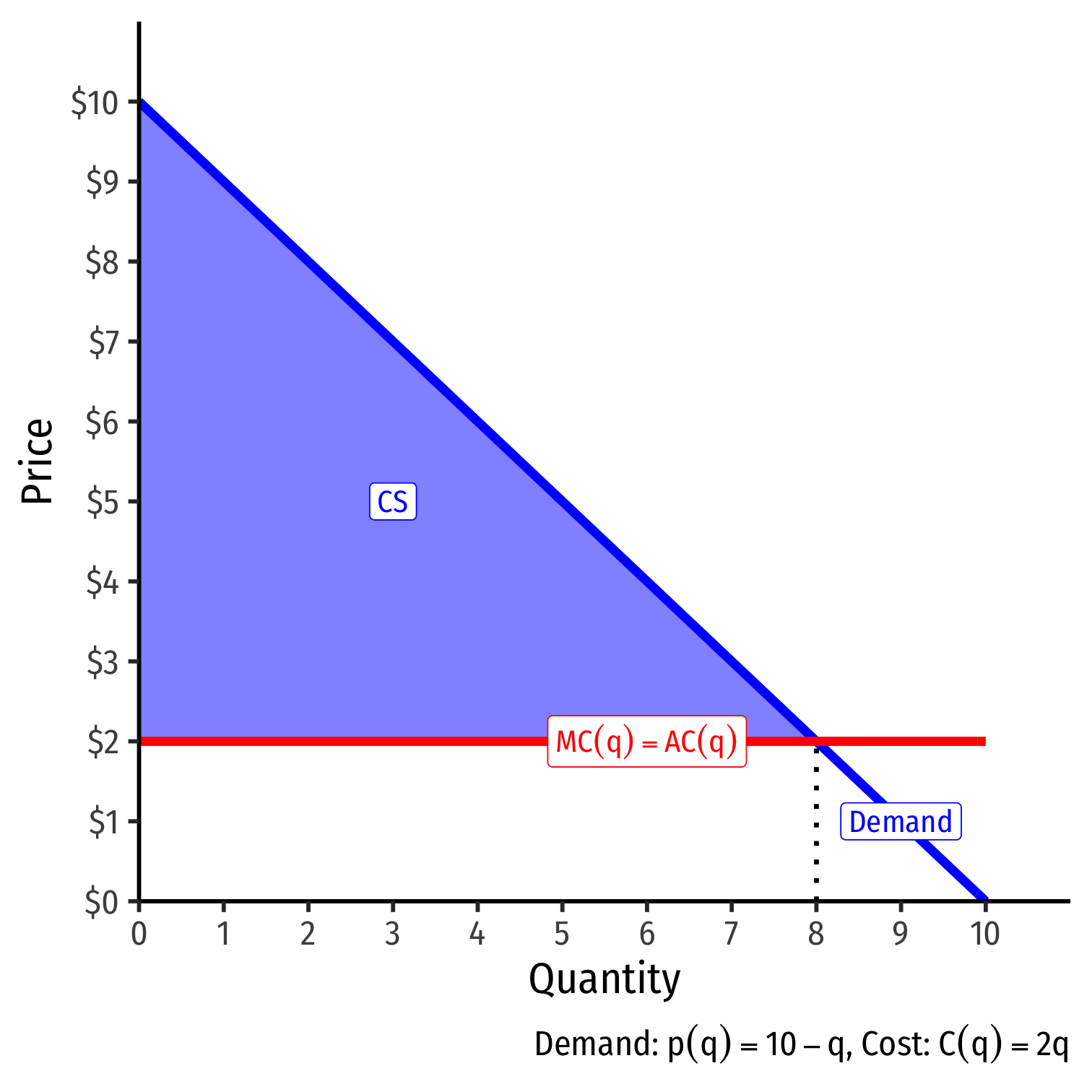

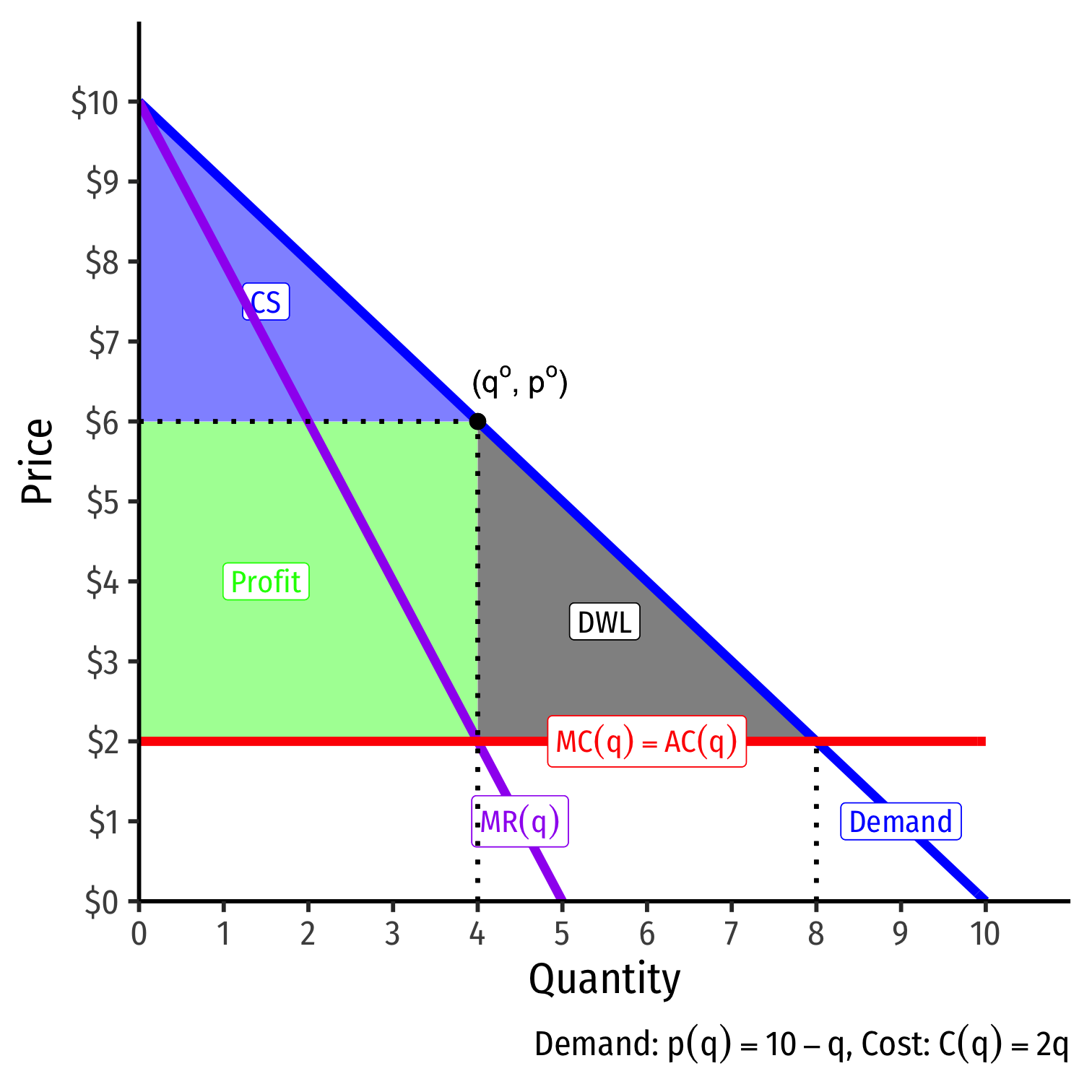

Profit Seeking: the Microeconomics I

Production generates economic surplus

In a competitive market in long run equilibrium, economic profit is driven to $0.

- p=AC(q)min, otherwise firms would enter/exit

- p=MC(q), allocatively efficient (goods produced until MB=MC)

- Consumer surplus and producer surplus is maximized

Some assumptions to make the graph simple: C(q)=aq∀a∈R+, i.e. the firm has no fixed costs, and constant marginal costs. See more information here.

From Profits to Rents

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices," (Book I, Chapter 22).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

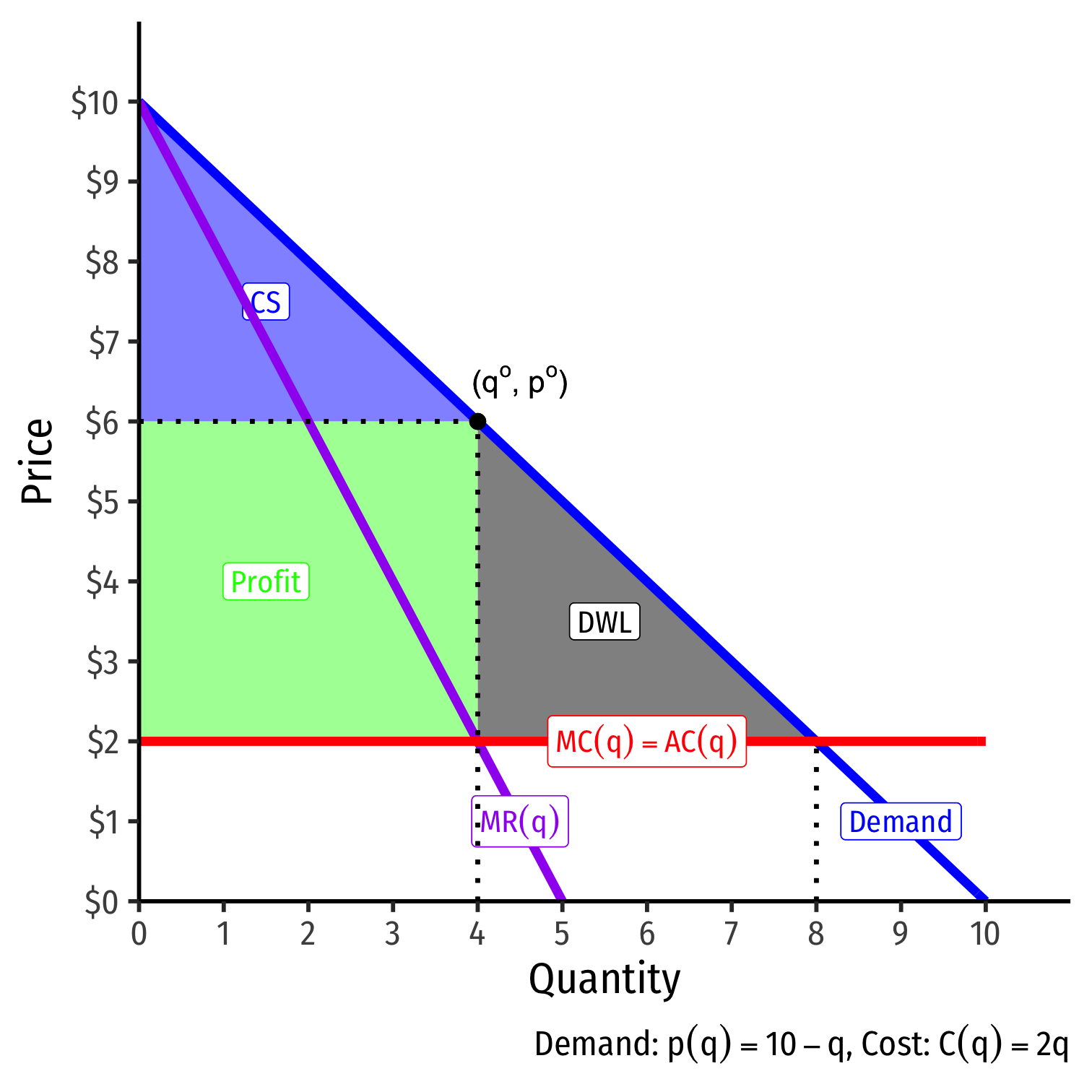

Profit Seeking: the Microeconomics II

Firms with market power will want to set q∗:MC(q)=MR(q) and raise price p∗

Still creates economic surplus

- Generates less consumer surplus than before

- Some surplus is captured as profit

- Some surplus is wasted as deadweight loss

Some assumptions to make the graph simple: (C(q)=aq \quad \forall a \in \mathbf{R}^+), i.e. the firm has no fixed costs, and constant marginal costs. See more information here.

Rent: Microeconomics I

- Firms may have different cost structures due to differences in:

- Managerial talent

- Worker talent

- Location

- First-mover advantage

- Technological secrets/IP

- License/permit access

- Political connections

- Lobbying

Rent: Microeconomics II

With differences between firms, long-run equilibrium p=AC(q)min of the marginal (highest-cost) firm

- If p>AC(q) for that firm, more entry into industry!

Inframarginal (lower-cost) firms earn economic rents: returns higher than their opportunity cost (what is needed to bring them online, p>AC(q)

Economic rents arise from relative differences between firms

Rent: Microeconomics III

Relatively scarce factors in the economy (talent, location, secrets, IP, licenses, being first, political favoritism, lobbying)

Inframarginal firms using the scarce factors gain a cost-advantage

It would seem these firms earn profits as other firms have higher costs

But what will happen to the prices for the scarce factors?

Rent: Microeconomics IV

Rents ≠ profits!

Rival firms willing to pay for rent-generating factor to gain advantage

Rents are included in the opportunity cost (price) for inputs

Firm does not earn the rents, they raise firm's costs and squeeze out profits!

Factor owners (workers, landowners, inventors, etc) earn the rents as higher payments for their services (wages, rents, interest, royalties, etc).

Recall: Ricardo on Rent in the Long Run

David Ricardo

1772-1823

- In Ricardo's view, land was the fixed factor

Marginal product of land would fall to 0, requiring more and more labor and capital to scrape off marginal land

- Profits to capital fall to 0

- Wages to laborers fall to subsistence level

- Rents to land skyrocket due to land being the fixed factor

Ricardian rents describe these excess returns due to scarcity

Institutions Channel Entrepreneurship

William Baumol

1922-2017

"If entrepreneurs are defined, simply, to be persons who are ingenious and creative in finding ways that add to their own wealth, power, and prestige, then it is to be expected that not all of them will be overly concerned with whether an activity that achieves these goals adds...to the social product," (pp897-898).

"The rules of the game that determine the relative payoffs to different entrepreneurial activities do change dramatically from one time and place to another. Entrepreneurial behavior changes direction from one economy to another in a manner that corresponds to the variations in the rules of the game," (p.898).

Baumol, William J, (1990), "Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive," Journal of Political Economy 98(5): 893-921

Profit Seeking and Rent Seeking

Productive entrepreneurship

Profits from serving customers

Unproductive entrepreneurship

Rents from political privileges

Destructive entrepreneurship

Loot from theft and violence

Profit Seeking vs. Rent Seeking: Some Generalizations

| Profit-Seeking | Rent-Seeking |

|---|---|

| "market entrepreneurs" | "political entrepreneurs" |

| hire engineers | hire lawyers |

| use own/investor funds | use taxpayer funds |

| sell to consumers | sell to the State |

| face the profit test | don't face the profit test |

| earn profits or losses | earn rents |

| create surplus for consumers | creates artificial protection from competition |

| hopes to capture some of that surplus | captures rents from that artificial protection |

A Story of Rent-Seeking vs. Profit-Seeking in the Early U.S. I

Robert Fulton

Fulson, Burton, (2010), The Myth of the Robber Barons: A New Look at the Rise of Big Business in America, 6th ed.

A Story of Rent-Seeking vs. Profit-Seeking in the Early U.S. II

Edward Gibbons

Cornelius Vanderbilt

Fulson, Burton, (2010), The Myth of the Robber Barons: A New Look at the Rise of Big Business in America, 6th ed.

A Story of Rent-Seeking vs. Profit-Seeking in the Early U.S. III

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824)

John Marshall

1755-1835

"A right over [licenses and patents] has never been pretended to in any instance except as incidental to the exercise of some other unquestionable power. The present is an instance of the assertion of that kind, as incidental to a municipal power; that of superintending the internal concerns of a State, and particularly of extending protection and patronage, in the shape of a monopoly, to genius and enterprise. The grant to Livingston and Fulton interferes with the freedom of intercourse, and on this principle, its constitutionality is contested.(p. 22 US 229)

"If there was any one object riding over every other in the adoption of the Constitution, it was to keep the commercial intercourse among the States free from all invidious and partial restraints," (p. 22 US 231)

Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824) Justia Case Law

The Allocation of Talent Matters I

"A country's most talented people typically organize production by others, so they can spread their ability advantage over a larger scale. When they start firms, they innovate and foster growth, but when they become rent seekers, they only redistribute wealth and reduce growth. Occupational choice depends on returns to ability and to scale in each sector, on market size, and on compensation contracts. In most countries, rent seeking rewards talent more than entrepreneurship does, leading to stagnation. Our evidence shows that countries with a higher proportion of engineering college majors grows faster; wheras countries with a higher proportion of law concentrators grow more slowly," (p. 503)

Murphy, Kevin M, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert M. Vishny, (1991). "The Allocation of Talent: Implications for Growth," Quarterly Journal of Economics 106(2): 503-530

The Allocation of Talent Matters II

Murphy, Kevin M, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert M. Vishny, (1991). "The Allocation of Talent: Implications for Growth," Quarterly Journal of Economics 106(2): 503-530

Economic Rents Induce Rent-Seeking

Think of an economic rent as a "prize," the payment a person receives for a good above its opportunity cost

Creating rents creates competition for the rents, causing people to invest resources in rent-seeking

The cost of the rent is not just the rent itself, but the resources invested in rent-seeking!

Government Intervention Creates Rents I

Political authorities intervene in markets in various ways that benefit some groups at the expense of everyone else

- subsidies to groups (often producers)

- regulation of industries

- tariffs, quotas, and special exemptions from these

- tax breaks and loopholes

- conferring monopoly and other privileges

These interventions create economic rents for their beneficiaries by reducing competition

This is a transfer of wealth from consumers/taxpayers to politically-favored groups

Government Intervention Creates Rent-Seeking

The transfer is not the worst of it

The real problem is you cannot give away money for free even if you tried!

The promise of earning a rent breeds competition over the rents (rent-seeking)

Rent-Seeking I

Anne Kreuger

1934-

"In many market-oriented economies, government restrictions upon economic activity are pervasive facts of life. These restrictions give rise to rents of a variety of forms, and people often compete for the rents. Sometimes, such competition is perfectly legal. In other instances, rent seeking takes other forms, such as bribery, corruption, smuggling, and black markets."

"When quantitative restrictions are imposed upon and effectively constrain imports, an import license is a valuable commodity...It has always been recognized that there are some costs associated with licensing: paperwork, the time spent by entrepreneurs in obtaining their licenses, the cost of the administrative apparatus necessary to issue licenses, and so on. Here, the argument is carried one step further: in many circumstances resources are devoted to competing for those licenses," (p.848).

Kreuger, Anne, (1974), "The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society," American Economic Review 84(4): 833-850

Rent-Seeking II

Kreuger, Anne, (1974), "The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society," American Economic Review 84(4): 833-850

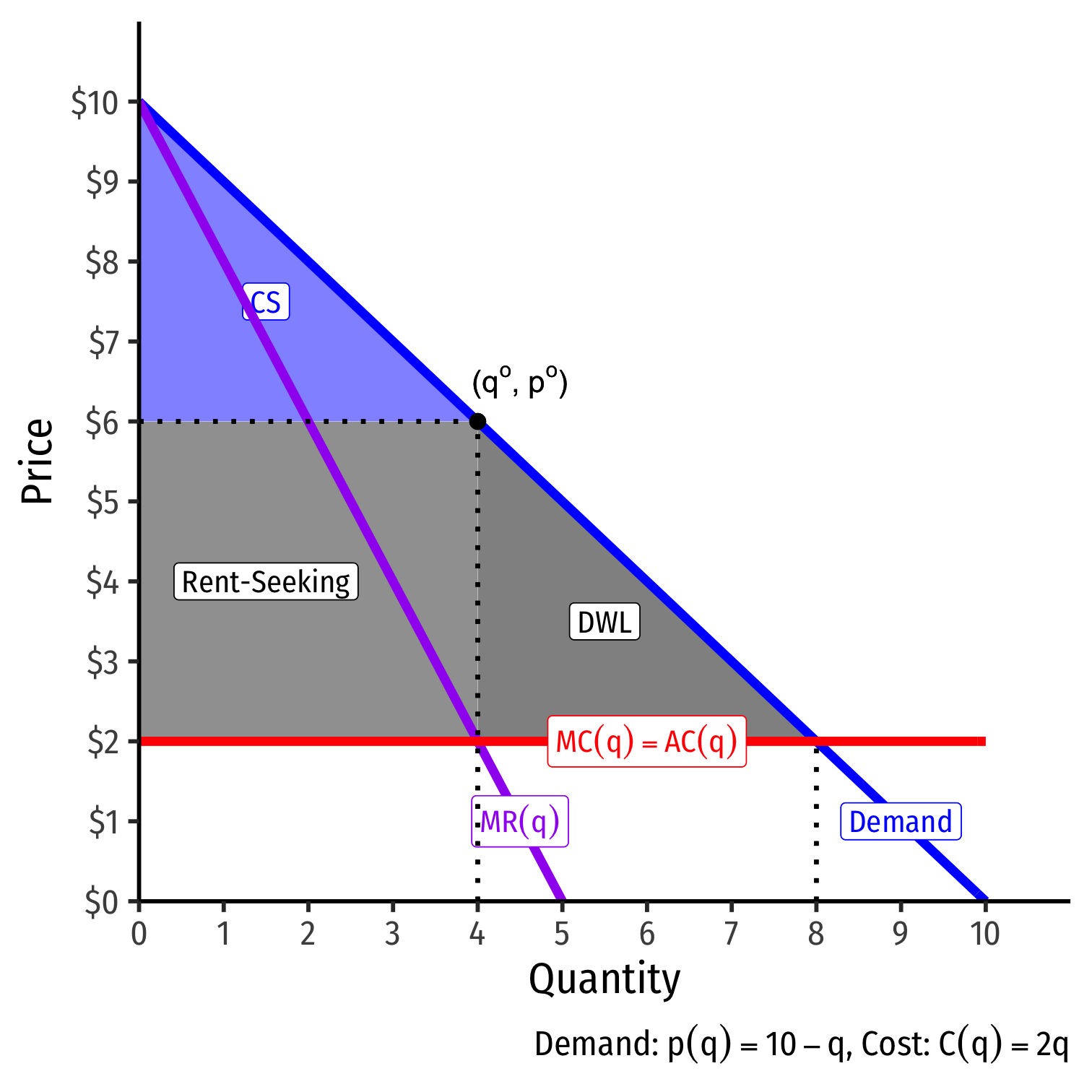

Rent-Seeking: The Ugly of Monopoly

The monopoly profits earned with market power are an economic rent

- This is the "prize" of market power

What if the market power is earned through political lobbying for an anti-competitive regulation?

Rent-Seeking: The Ugly of Monopoly

The monopoly profits earned with market power are an economic rent

- This is the "prize" of market power

What if the market power is earned through political lobbying for an anti-competitive regulation?

Firm(s) willing to invest resources into the "competitive market" of creating and maintaining economic rents

Total loss to society =DWL+Rent-seeking (of all competitors!)

Rent-Seeking III

Gordon Tullock

1922-2014

"The rectangle to the left of the [Deadweight loss] triangle is the income transfer that a successful monopolist can extort from the customers. Surely we should expect that with a prize of this size dangling before our eyes, potential monopolists would be willing to invest large resources in the activity of monopolizing. In fact the investment that could be profitably made in forming a monopoly would be larger than this rectangle, since it represents merely the income transfer," (p.231).

Tullock, Gordon, (1967), "The Welfare Cost of Tariffs, Monopolies, and Theft," Western Economic Journal 5(3): 224-232.

Rent-Seeking IV

Gordon Tullock

1922-2014

"Entrepreneurs should be willing to invest resources in attempts to form a monopoly until the marginal cost equals the properly discounted return. The potential customers would also be interested in preventing the transfer and should be willing to make large investments to that end. Once the monopoly is formed, continual efforts to either break the monopoly or muscle into it would be predictable. Here again considerable resources might be invested. The holders of the monopoly, on the other hand, would be willing to put quite sizable sums into the defense of their power to receive these transfers," (p.231).

Tullock, Gordon, (1967), "The Welfare Cost of Tariffs, Monopolies, and Theft," Western Economic Journal 5(3): 224-232.

Rent-Seeking V

A Microcosm of the Political Economy of Creative Destruction I

A Microcosm of the Political Economy of Creative Destruction II

If You Look at the World Long Enough...

Regulation has a Dark Side

George Stigler

1911-1991

Economics Nobel 1982

"[A]s a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefits," (p.3).

Stigler, George J, (1971), "The Theory of Economic Regulation," Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 3:3-21

Private Rent-Seeking I

The Rievers (1969) based on William Faulkner’s (1962) book

Private Rent-Seeking II

Private Rent-Seeking III

Back to Institutions: Rent-Seeking and Elites

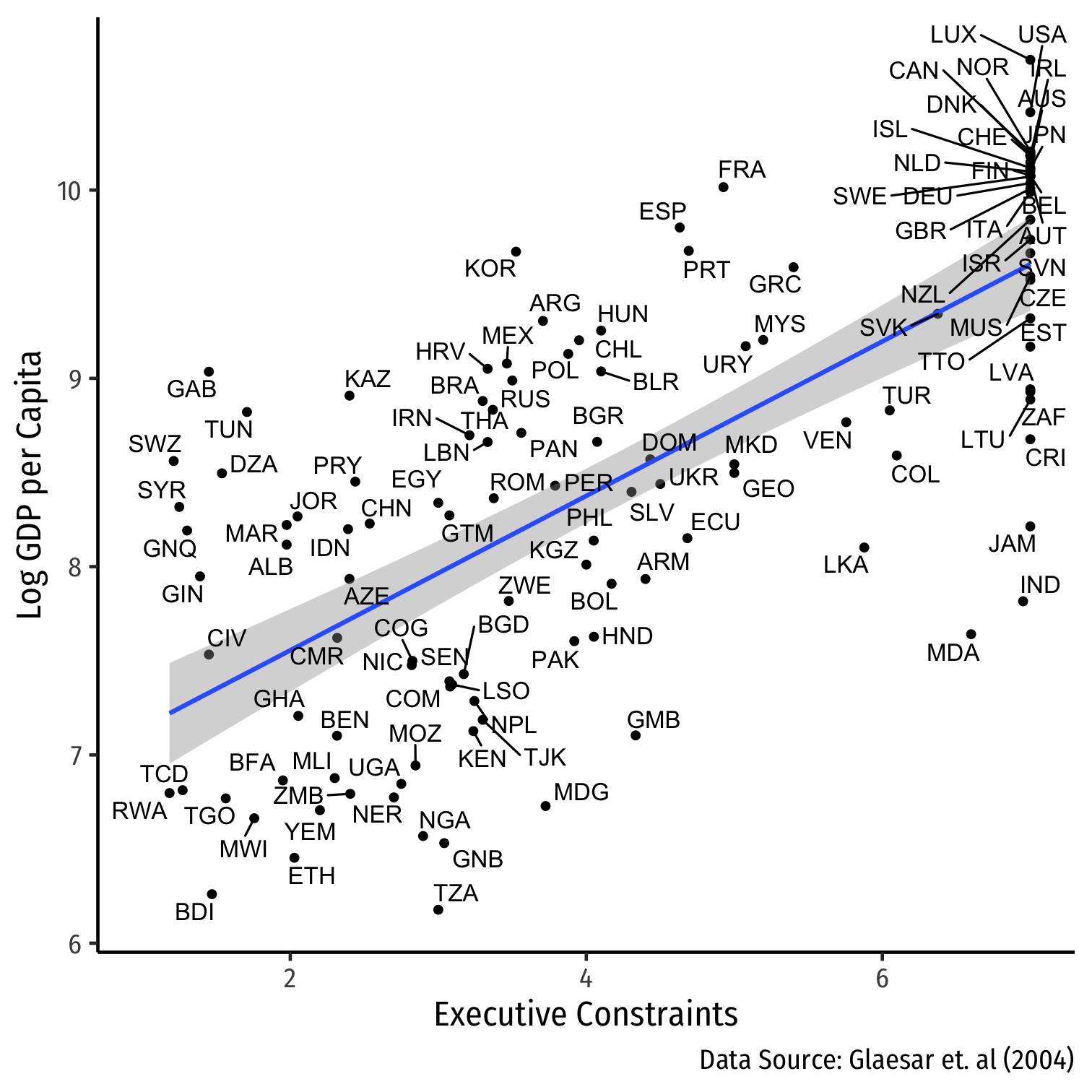

Institutions Matter

Executive Constraints: A measure of the extent of institutionalized constraints on the decision making powers of chief executives. The variable takes seven different values: (1) Unlimited authority(there are no regular limitations on the executive's actions, as distinct from irregular limitations such as the threat or actuality of coups and assassinations); (2) Intermediate category; (3) Slight to moderate limitation on executive authority (there are some real but limited restraints on the executive); (4) Intermediate category; (5) Substantial limitations on executive authority (the executive has more effective authority than any accountability group but is subject to substantial constraints by them); (6) Intermediate category; (7) Executive parity or subordination (accountability groups have effective authority equal to or greater than the executive in most areas of activity). This variable ranges from one to seven where higher values equal a greater extent of institutionalized constraints on the power of chief executives. This variable is calculated as the average from 1960 through 2000, or for specific years as needed in the tables. Source:Jaggers and Marshall (2000).

Glaesar, Edward L, Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer, 2004, "Do Institutions Cause Growth?" Journal of Economic Growth 9: 271-303

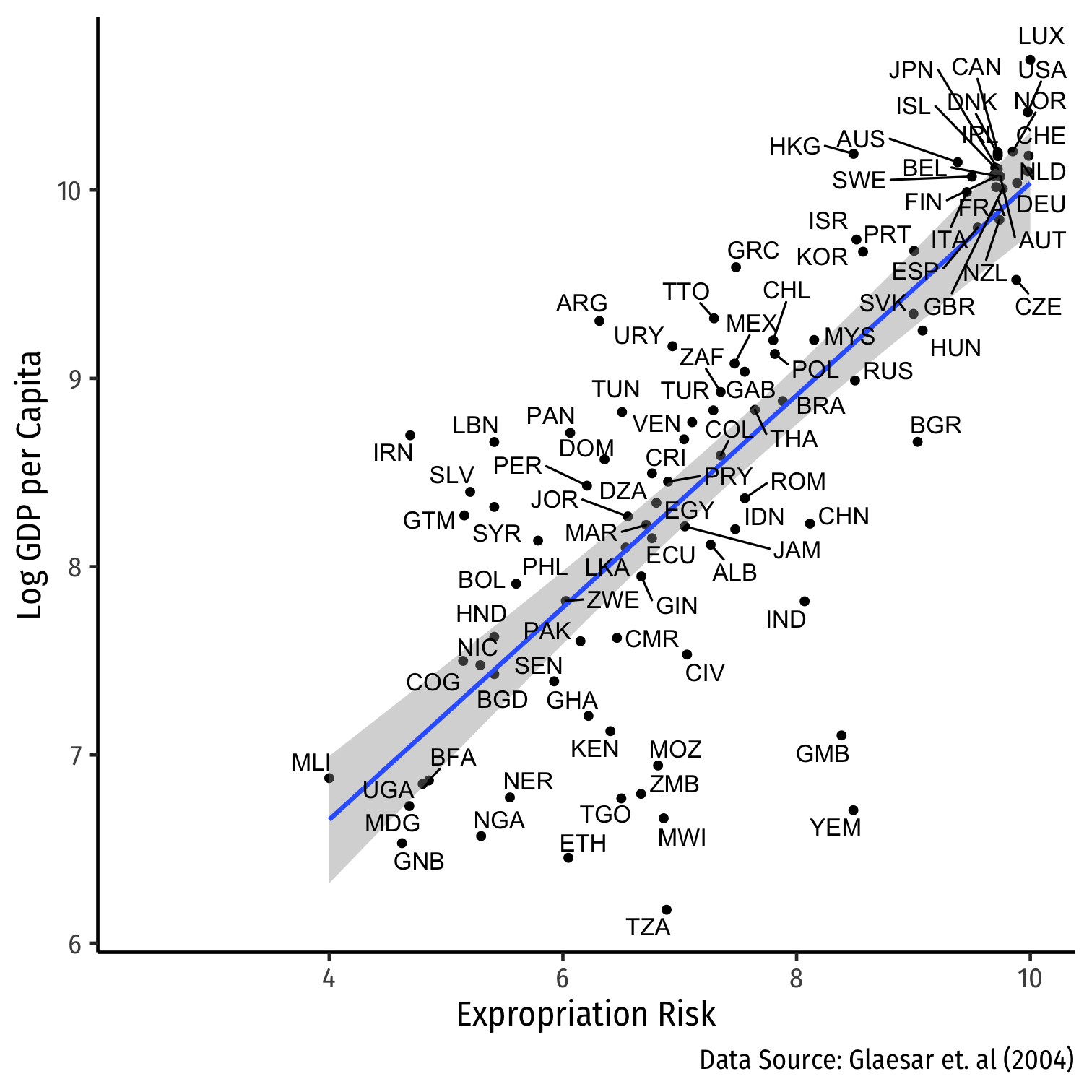

Institutions Matter II

Expropriation Risk: Risk of "outright confiscation and forced nationalization" of property. This variable ranges from zero to ten where higher values are equals a lower probability of expropriation. This variable is calculated as the average from 1982 through 1997, or for specific years as needed in the tables. Source: International Country Risk Guide at http://www.countrydata.com/datasets/.

Glaesar, Edward L, Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer, 2004, "Do Institutions Cause Growth?" Journal of Economic Growth 9: 271-303

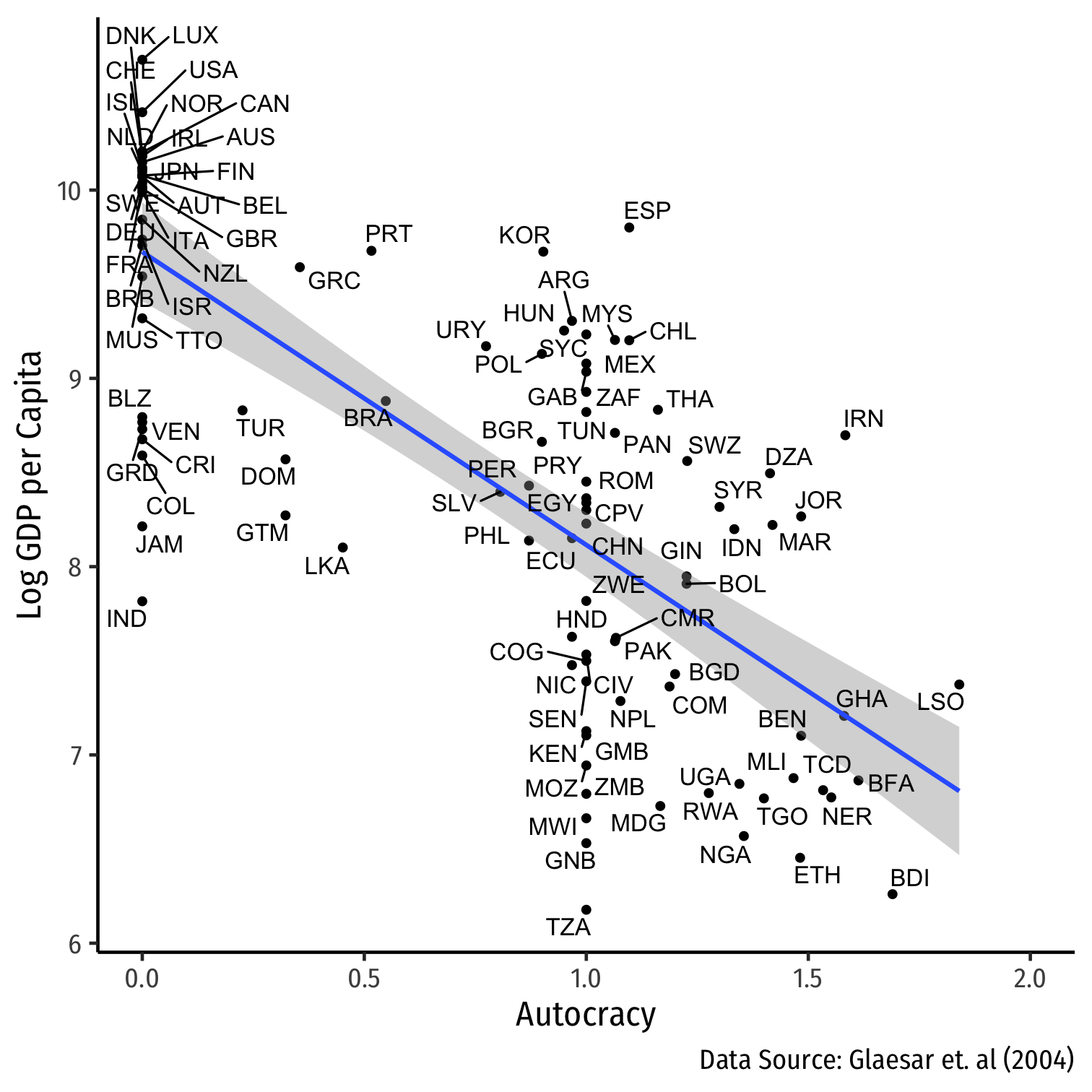

Institutions Matter III

Autocracy: A measure of the degree of autocracy in a given country based on: (1) the competitiveness of political participation; (2) the regulation of political participation; (3) the openness and competitiveness of executive recruitment; and (4) constraints on the chief executive. This variable ranges from zero to ten where higher values equal a higher degree of institutionalized autocracy. This variable is calculated as the average from 1960 through 2000, or for specific years as needed in the tables. Source:J aggers and Marshall (2000).

Glaesar, Edward L, Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer, 2004, "Do Institutions Cause Growth?" Journal of Economic Growth 9: 271-303

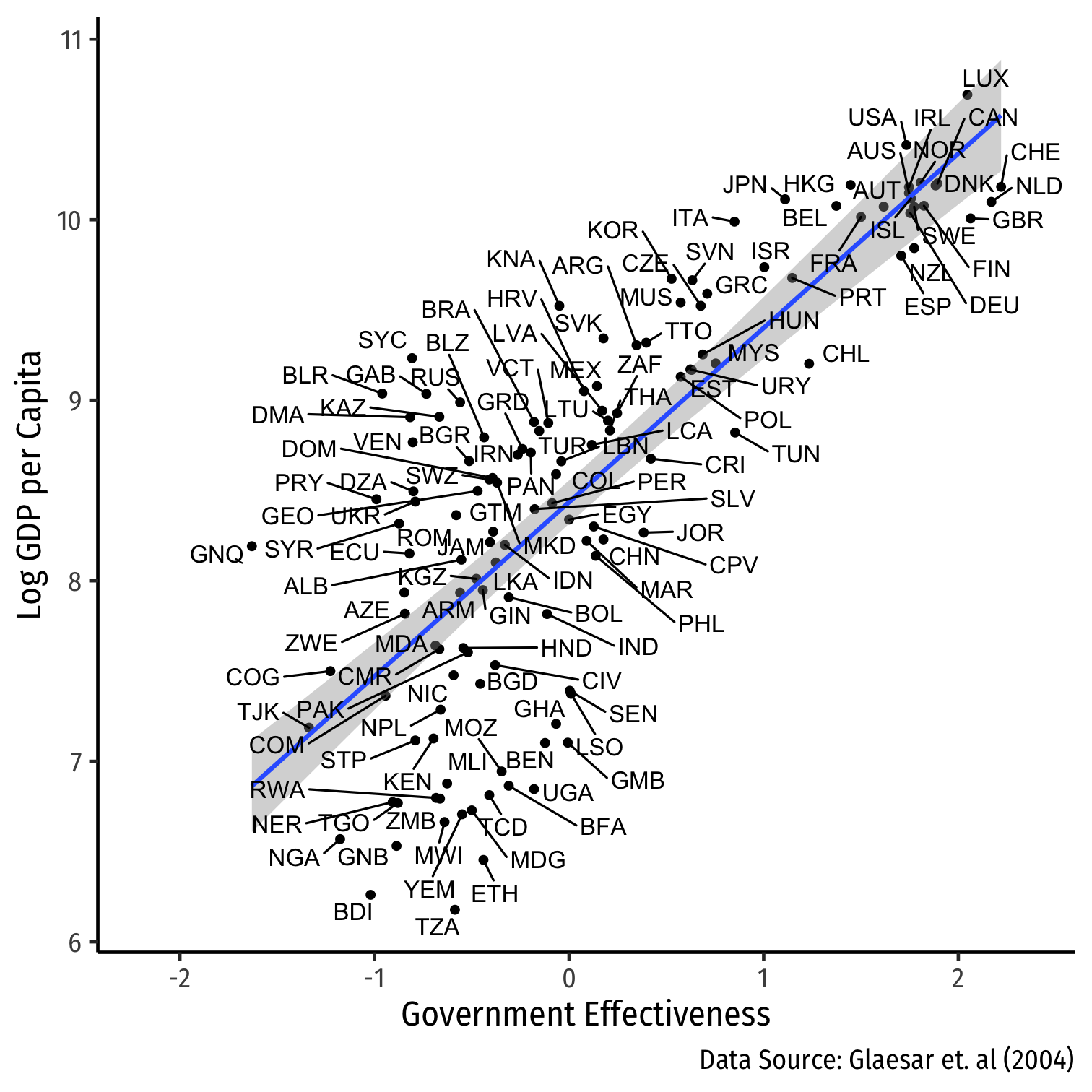

Institutions Matter IV

Government effectiveness: This variable measures the quality of public service provision, the quality of the bureaucracy, the competence of civil servants, the independence of the civil service from political pressures, and the credibility of the government's commitment to policies. The main focus of this index is on "inputs" required for the government to be able to produce and implement good policies and deliver public goods. This variable ranges from −2.5 to 2.5 where higher values equal higher government effectiveness. This variable is measured as the average from 1998 through 2000. Source: Kaufman et al. (2003).

Glaesar, Edward L, Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer, 2004, "Do Institutions Cause Growth?" Journal of Economic Growth 9: 271-303

Political Institutions

Politics: process by which society chooses rules that will govern it

AJR1:

Economic performance ← economic institutions ← politics ← political institutions ← distribution of political power

- Key role of state capacity or "political centralization" in development

1 The colloquial term for "Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson" who frequently collaborate together on these issues!

AJR: Inclusive vs. Extractive Institutions

Extractive Institutions/Colonies

Inclusive Institutions/Colonies

Political Institutions

Strong feedback loops:

under extractive institutions, political & economic elite can structure institutions to maintain their wealth and power to extract rents at the expense of the population

under inclusive institutions, more equitable distribution of wealth and power, competition prevents any one group from creating and maintaining enough rents to exert control

institutions are maintained by elites who control power, choose economic institutions with few constraints or opposing forces to them!

Why would elites ever permit reform?

AJR's Ultimate Framework

Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, 2006, "Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth," Handbook of Economic Growth, Phillippe Aghion and Steven N. Durlauf, eds., pp.385-414

Economic Losers as Barriers to Development?

Luddites

The "Luddites" destroying power looms in early 19th century Britain

AJR: Political Losers, Not Economic Losers, Block Development

"There are problems with this story, however. First, despite the intuitive appeal of the idea, there are relatively few instances where major economic changewas blockedby economic losers. Mokyr (1990) emphasizes the attemptsof many skilled artisansto block the introduction of new machines.The most famous example is the Luddites,skilled weavers who were thrown out of work by mechanization. Interestingly, however, many of these groups, including the Luddites, were ultimately unable to block economic progress. Equally important, the economic-losers hypothesis relies on the presumption that certain groups have the political power to block innovation. But if so, why not use this power to simply tax the gains generated by the introductionof the new technology? This might be because there are limits on the nature of fiscal instruments,though it seems plausible that groups with sufficient political power to block innovationwould be able subsequentlyto lobby effectively for redistribution. A more important reason, however, may be that the introductionof new technology, and economic change more generally, may simultaneously affect the distributionof political power," (126).

Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson, 2000, "Political Losers as a Barrier to Economic Development," American Economic Review 90(2): 126-130

AJR: Political Losers, Not Economic Losers, Block Development

"We arguethatthe effect of economic change on political power is a key factor in determining whether technological advances and beneficial economic changes will be blocked. In other words, we propose a "political-loser hypothesis." We argue that it is groupswhose political power (not economic rents) is eroded who will block technological advances.If agents are economic losers but have no political power, they cannot impede technological progress. If they have and maintain political power (i.e., are not political losers), then they have no incentive to block progress.It is therefore agents who have political power and fear losing it who will have incentives to block. Our analysis suggests that we should look more to the nature of political institutions and the determinants of the distribution of political power if we want to understand technological backwardness," (pp.126-127)

Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson, 2000, "Political Losers as a Barrier to Economic Development," American Economic Review 90(2): 126-130