Lesson 9: The Malthusian Pre-Modern Economy

ECON 317 · Economics of Development · Fall 2019

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/devf19

devF19.classes.ryansafner.com

The Malthusian Trap

3,000 Years of Economic History in One Graph

Clark, Gregory, (2007), A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World, p.2

Malthus on Population and Growth I

Rev. Thomas Malthus

1766-1834

"Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio. A slight acquaintance with numbers will shew the immensity of the first power in comparison of the second."

"The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race."

Malthus, Thomas, 1798, An Essay on the Principle of Population

Malthus on Population and Growth II

Rev. Thomas Malthus

1766-1834

"The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race. The vices of mankind are active and able ministers of depopulation. They are the precursors in the great army of destruction, and often finish the dreadful work themselves. But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and tens of thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world."

Malthus, Thomas, 1798, An Essay on the Principle of Population

Malthusian Economies I

Rev. Thomas Malthus

1766-1834

Classical economist like Ricardo: assume diminishing returns to land, and land is a fixed factor

Two Malthusian implications

Population increases with living standards

- suppose technology improves agricultural productivity

- higher wages and incomes, people are wealthier and can support more children

- hence, population grows

Living standards decline with population

- A growing population with a fixed supply of land with diminishing returns implies living standards eventually decrease

- population will die off and return to subsistence equilibrium

- In sum: living standards and population are inversely proportional!

- you can think GDP per capita =GDPpopulation where population is increasing!

Malthusian Economies I

Rev. Thomas Malthus

1766-1834

In sum: living standards and population are inversely proportional!

Think GDP per capita$=\frac{GDP}{population}$ where population is increasing!

Malthusian Economies III

Galor, Oded, 2012, Unified Growth Theory

Malthusian Economies IV

Ashraf, Quamrul and Oded Galor, 2011, "Dynamics and Stagnation in the Malthusian Epoch," American Economic Review 101: 2003-2048

Malthusian Economies V

Ashraf, Quamrul and Oded Galor, 2011, "Dynamics and Stagnation in the Malthusian Epoch," American Economic Review 101: 2003-2048

Malthusian Economies VI

"This paper examines the central hypothesis of the influential Malthusian theory, according to which improvements in the tech-nological environment during the preindustrial era had generated only temporary gains in income per capita, eventually leading to a larger, but not significantly richer, population. Exploiting exogenous sources of cross-country variations in land productivity and the level of technological advancement, the analysis demonstrates that, in accordance with the theory, technological superiority and higher land productivity had significant positive effects on population den-sity but insignificant effects on the standard of living, during the time period 1–1500 CE."

Ashraf, Quamrul and Oded Galor, 2011, "Dynamics and Stagnation in the Malthusian Epoch," American Economic Review 101: 2003-2048

The Malthusian Trap I

Rev. Thomas Malthus

1766-1834

- "Malthusian" Trap: for most of human history, humans have been unable to escape poverty because of the following cycle:

Living standards improve→population growth→

- Humanity stuck in a subsistence-level equilibrium for 1000s of years

Malthus, Thomas, 1798, An Essay on the Principle of Population

The Malthusian Trap II

Malthusian Virtues and Vices

If you buy the Malthusian argument: ordinary virtues are Malthusian vices, and ordinary vices are Malthusian virtues

Policies that help improve living standards and life expectancy, particularly among the poor and sickly make Malthusian pressures of overpopulation even greater!

#ThanosDidNothingWrong...According to Malthus

#ThanosDidNothingWrong...According to Malthus

Malthus is Misunderstood

Yes, Malthus was "wrong" in the long-run

missed the enormous rise in productivity

but he accurately described the history of the world up until 1800

Digression: the Economics of Population and Development

World Population Growth Is Expected to Continue Declining

Source: Our World in Data: Population Growth

Because Economies Experience a "Demographic Transition"

Source: Our World in Data: Population Growth

Two Views of the Economics of Population I

"People as Stomachs"

Paul Ehrlich

1932-

"People as Brains"

Julian Simon

1932-1998

People as "Stomachs" I

"The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate."

"We must have population control at home, hopefully through a system of incentives and penalties, but by compulsion if voluntary methods fail."

"65 million Americans will die of starvation between 1980-1989. By 1999, the US population will decline to 22.6 million."

"If I were a gambler, I would take even money that England will not exist in the year 2000."

Ehrlich, Paul, 1968, The Population Bomb

Donella Meadows et al., 1972, The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind.

People as "Stomachs" II

- Predictions: the world would run out of

- gold by 1981

- mercury and silver by 1985

- tin by 1987

- zinc by 1990

- petroleum by 1992

- copper, lead and natural gas by 1993

- aluminum between 2005-2021

Ehrlich, Paul, 1968, The Population Bomb

Donella Meadows et al., 1972, The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind.

People as "Stomachs": The Problems with Farming I

"For most of our history we supported ourselves by hunting and gathering: we hunted wild animals and foraged for wild plants. It's a life that philosophers have traditionally regarded as nasty, brutish, and short. Since no food is grown and little is stored, there is (in this view) no respite from the struggle that starts anew each day to find wild foods and avoid starving...[The question] "Why did almost all our hunter-gatherer ancestors adopt agriculture?" is silly. Of course they adopted it because agriculture is an efficient way to get more food for less work. Planted crops yield far more tons per acre than roots and berries."

People as "Stomachs": The Problems with Farming II

"There are at least three sets of reasons to explain the findings that agriculture was bad for health. First, hunter-gatherers enjoyed a varied diet, while early farmers obtained most of their food from one or a few starchy crops. The farmers gained cheap calories at the cost of poor nutrition, (today just three high-carbohydrate plants — wheat, rice, and corn — provide the bulk of the calories consumed by the human species, yet each one is deficient in certain vitamins or amino acids essential to life.) Second, because of dependence on a limited number of crops, farmers ran the risk of starvation if one crop failed. Finally, the mere fact that agriculture encouraged people to clump together in crowded societies, many of which then carried on trade with other crowded societies, led to the spread of parasites and infectious disease. (Some archaeologists think it was the crowding, rather than agriculture, that promoted disease, but this is a chicken-and-egg argument, because crowding encourages agriculture and vice versa.) Epidemics couldn't take hold when populations were scattered in small bands that constantly shifted camp. Tuberculosis and diarrheal disease had to await the rise of farming, measles and bubonic plague the appearance of large cities."

People as "Brains" I

Basic price theory: demand for resource raises its price

- Induces recycling, more efficient utilization of resources, development of substitute goods and innovations

- "It takes much less copper now to pass a given message than a hundred years ago."

"Engineering" vs. "economic" forecasting:

- "Engineering forcecasting" takes the amount of physical resources known to be available and substracts an extraplolation of current use rates from this

- these are often famously wrong

- "Economic" forecasting: need to include undiscovered sources, sources not yet economically feasible to extract, sources not yet technologically feasible to extract (note they are different!)

Simon, Julian L, 1981, The Ultimate Resource

People as "Brains" II

The ultimate resource is people!

More people ⟹ greater extent of the market ⟹ more division of labor ⟹ more specialization ⟹ more productivity

More chances to have an Einstein or a Mozart

Simon, Julian L, 1981, The Ultimate Resource

People as Stomachs vs. Brains

"The nonrivalry of technology, as modeled in the endogenous growth literature, implies that high population spurs technological change. This paper constructs and empirically tests a model of long-run world population growth combining this implication with the Malthusian assumption that technology limits population. The model predicts that over most of history, the growth rate of population will be proportional to its level. Empirical tests support this prediction and show that historically, among societies with no possibility for technological contact, those with larger initial populations have had faster technological change and population growth," (p.681)

"[H]olding constant the share of resources devoted to research, an increase in population leads to an increase in technological change...This paper argues that the long-run history of population growth and technological change is consistent with the population implications of models of endogenous technological change...even if each person's research productivity is independent of population, total research output will increase with population due to the nonrivalry of technology. As Kuznets [1960] and Simon [1977, 1981] argue, a higher population means more potential inventors.," (p.681-684)

Kremer, Michael, 1993, "Population Growth and Technological Change: One Million B.C. to 1990," Quarterly Journal of Economics 108(3): 681-716.

Economics of the State: Roving and Stationary Bandits

Thomas Hobbes: Political Economy's First Game Theorist I

Thomas Hobbes

1588-1679

"In [the state of nature], there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth...no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short, (Ch. XVIII).

Hobbes, Thomas, 1651, Leviathan: Or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil

Thomas Hobbes: Political Economy's First Game Theorist II

Thomas Hobbes: Political Economy's First Game Theorist III

Thomas Hobbes

1588-1679

"For the Lawes of Nature (as Justice, Equity, Modesty, Mercy, and (in summe) Doing To Others, As Wee Would Be Done To,) if themselves, without the terrour of some Power, to cause them to be observed, are contrary to our naturall Passions, that carry us to Partiality, Pride, Revenge, and the like. And Covenants, without the Sword, are but Words, and of no strength to secure a man at all, (Ch. XVIII).

Hobbes, Thomas, 1651, Leviathan: Or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil

The Hobbesian Dilemma

Consider society, in general, a prisoner's dilemma for social cooperation or conflict:

- a: everyone else obeys the law, but I don't

- b: everyone obeys the law

- c: no one obeys the law

- d: I obey the law, but no one else does

Nash equilibrium: everyone defects!

Socially optimal equilibrium: everyone cooperates

Hobbes' insight: no individual has an incentive to cooperate when everyone defects!

Column |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperate | Defect | ||

| Row | Cooperate | b, b | d, a |

| Defect | a, d | c, c | |

a≻b≻c≻d

The Hobbesian Solution I

The Hobbesian Solution II

The State is our commitment device

Citizens (in principle) sign a social contract, i.e. a "constitution" that deliberately restricts their liberties

In each of our interests to give up some liberties that restrict the liberties of others (e.g. theft, violence)

In exchange, we empower the State as our agent to punish those of us that fail to uphold the social contract

Politics: decisions under rules which we agree are legitimate that determine an outcome for all of us, even if we disagree (or are harmed by) the outcome

The State

Max Weber

1864-1920

"[A] State is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory."

Weber, Max, 1919, Politics as a Vocation

Madison's Paradox I

James Madison

1751-1836

"If men were angels, no government would be nec- essary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself," (Federalist 51).

1788, The Federalist Papers

Madison's Paradox II

- Madison's Paradox: a State strong enough to protect rights is strong enough to violate them at its discretion

Credible Commitment

Odysseus and the Sirens by John William Waterhouse, Scene from Homer's The Odyssey

Credible Commitment

Odysseus and the Sirens by John William Waterhouse, Scene from Homer's The Odyssey

Hunter-Gatherer Societies I

Mancur Olson

1932-1998

"The simplest food-gathering and hunting societies are normally made up of bands that have...only about 50 or 100 people. Anthropologists find that primitive tribes normally maintain peace and order by voluntary agreement...The most primitive tribes tend to make all important collective decisions by consensus, and many of them do not even have chiefs...there is also little or no incentive for anyone to subjugate another tribe or keep slaves, since captives cannot generate enough surplus above subsistence to justify the costs of guarding them," (p.567).

Olson, Mancur, 1993, "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development," American Political Science Review 87(3): 567-576

Hunter-Gatherer Societies II

Mancur Olson

1932-1998

"Once peoples learned how to raise crops effectively, production increased, population grew, and large populations needed governments...voluntary collective action cannot obtain the gains from a peaceful order or other public goods, even when the aggregate net gains from the provision of public goods are large."

"[W]e should not be surprised that while there have been lots of writings about the desirability of "social contracts" to obtain the benefits of law and order, no one has ever found a large society that obtained a peaceful order or other goods through an agreement among the individuals in the society," (p.568).

Olson, Mancur, 1993, "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development," American Political Science Review 87(3): 567-576

The Neolithic Revolution

Neolithic Revolution (c.10,000 B.C.): development of agriculture, organized settlements, cities, and human civilization

Brings about a large surplus of food and wealth stored in a single location

The Neolithic Revolution

Neolithic Revolution (c.10,000 B.C.): development of agriculture, organized settlements, cities, and human civilization

Brings about a large surplus of food and wealth stored in a single location

- a ripe target for those with a comparative advantage in violence

Roving Bandits I

Mancur Olson

1932-1998

"In a world of roving banditry there is little or no incentive for anyone to produce or accumulate anything that may be stolen and, thus, little for bandits to steal," (p.568).

Olson, Mancur, 1993, "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development," American Political Science Review 87(3): 567-576

Roving Bandits I

Roving Bandits III

Roving Bandits IV

Anarchy under roving bandits is a tragedy of the commons

Too many roving bandits try to exploit local populations

Violence is overproduced

If only one bandit had "property rights" to exclude other bandits...

The Stationary Bandit I

Mancur Olson

1932-1998

"Bandit rationality, accordingly, induces the bandit leader to seize a given domain, to make himself a ruler of that domain, and to provide a peaceful order and other public goods for its inhabitants, thereby obtaining more in tax theft than he could have obtained from migratory plunder. Thus we have seen "the first blessing of the invisible hand:" the rational, self-interested leader of a band of roving bandits is led, as though by an invisible hand, to settle down, wear a crown, and replace anarchy with government," (p.568).

Olson, Mancur, 1993, "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development," American Political Science Review 87(3): 567-576

The Stationary Bandit II

The Stationary Bandit III

Mancur Olson

1932-1998

"In fact, if a roving bandit settles down and takes his theft in the form of regular taxation and at the same time maintains a monopoly on theft in his domain, then those whom he exacts taxes will have an incentive to produce. The rational stationary bandit will take only a part of income in taxes because he will be able to exact a larger total amount of income from his subjects if he leaves them with an incentive to generate an income he can tax. If the stationary bandit successfully monopolizes the theft in his domain, then his victims do not need to worry about theft by others," (pp.567-8).

Olson, Mancur, 1993, "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development," American Political Science Review 87(3): 567-576

The Stationary Bandit IV

Mancur Olson

1932-1998

"Thus government for groups larger than tribes normally arises, not be cause of social contracts or voluntary transactions of any kind, but rather because of rational self-interest among those who can organize the greatest capacity for violence. These violent entrepreneurs naturally do not call themselves bandits but, on the contrary, give themselves and their descendants exalted titles..Since history is written by the winners, the origins of ruling dynasties are, of course, conventionally explained in terms of lofty motives rather than by self-interest," (p.568).

Olson, Mancur, 1993, "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development," American Political Science Review 87(3): 567-576

The Stationary Bandit V

Mancur Olson

1932-1998

"[I]t will also pay him to provide other public goods whenever the provision of these goods increases taxable income sufficiently...The gigantic increase in output that normally arises from the provision of a peaceful order and other public goods gives the stationary bandit a far larger take than he could obtain without providing government," (p.568).

Olson, Mancur, 1993, "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development," American Political Science Review 87(3): 567-576

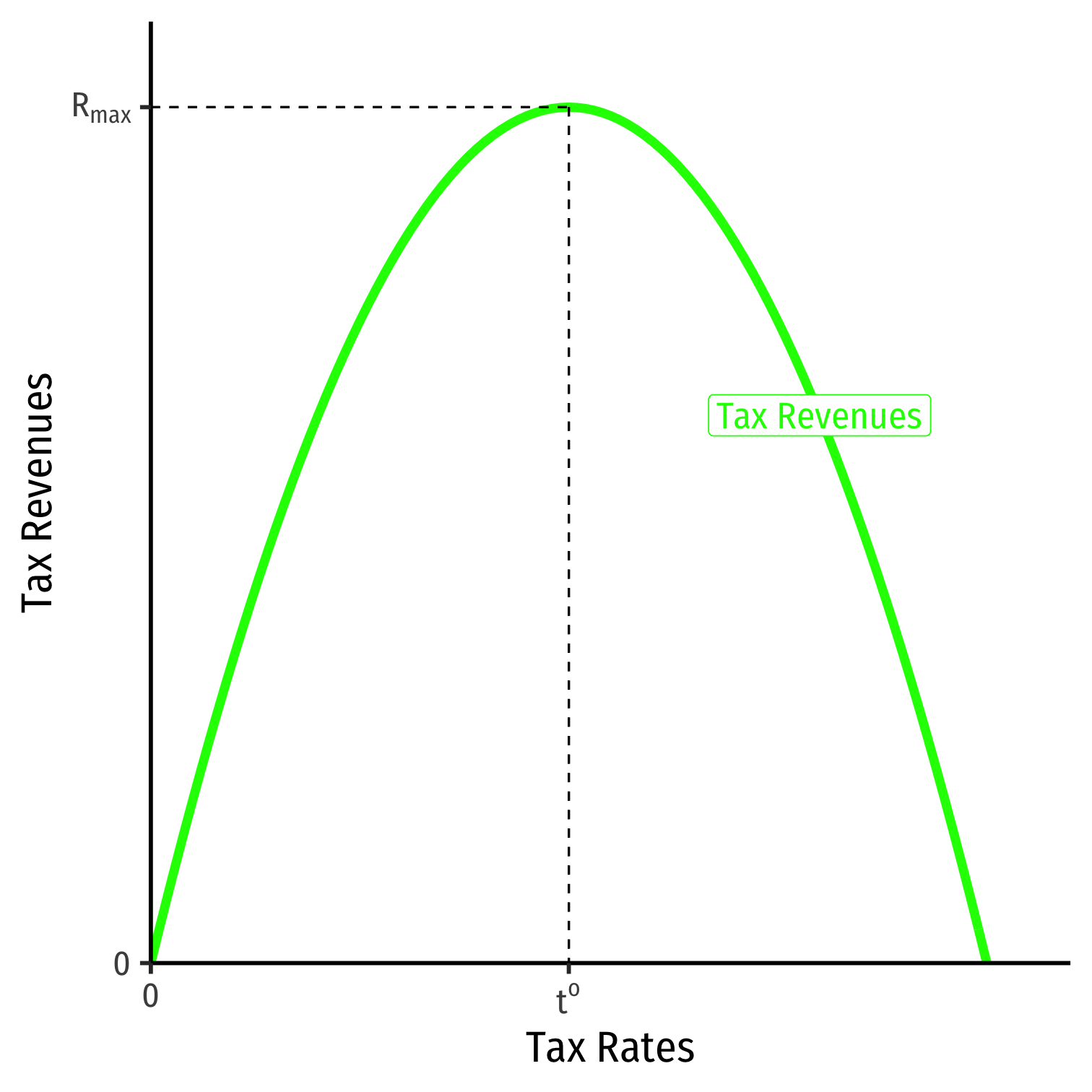

The Stationary Bandit's Economic Problem

Choose: < a tax rate >

In order to maximize: < own revenue >

Subject to: < staying in power >

Recall from Micro: Economic Taxation and Incentives

Taxes change incentives!

Taxes have two effects:

- Raise revenue for State

- Discourage individuals from taxed activity

- reduce activity

- find untaxed substitutes (legal or illegal)

- engage in hoarding, tax evasion

Optimal tradeoff between two effects for revenue-maximizing ruler

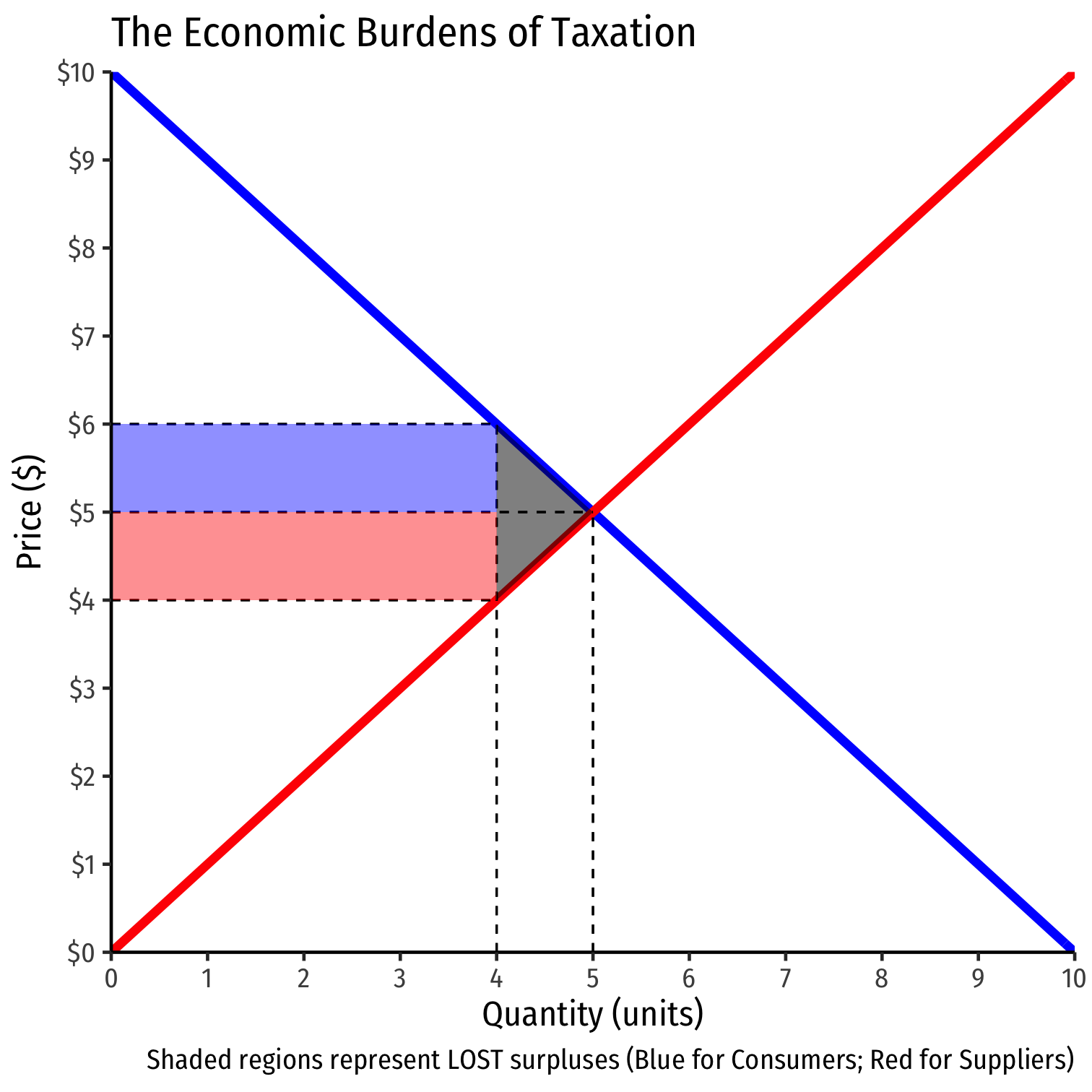

Recall from Micro: Economic Incidence of Taxation

- Tax of t:

- G1=8

- DWL1=1

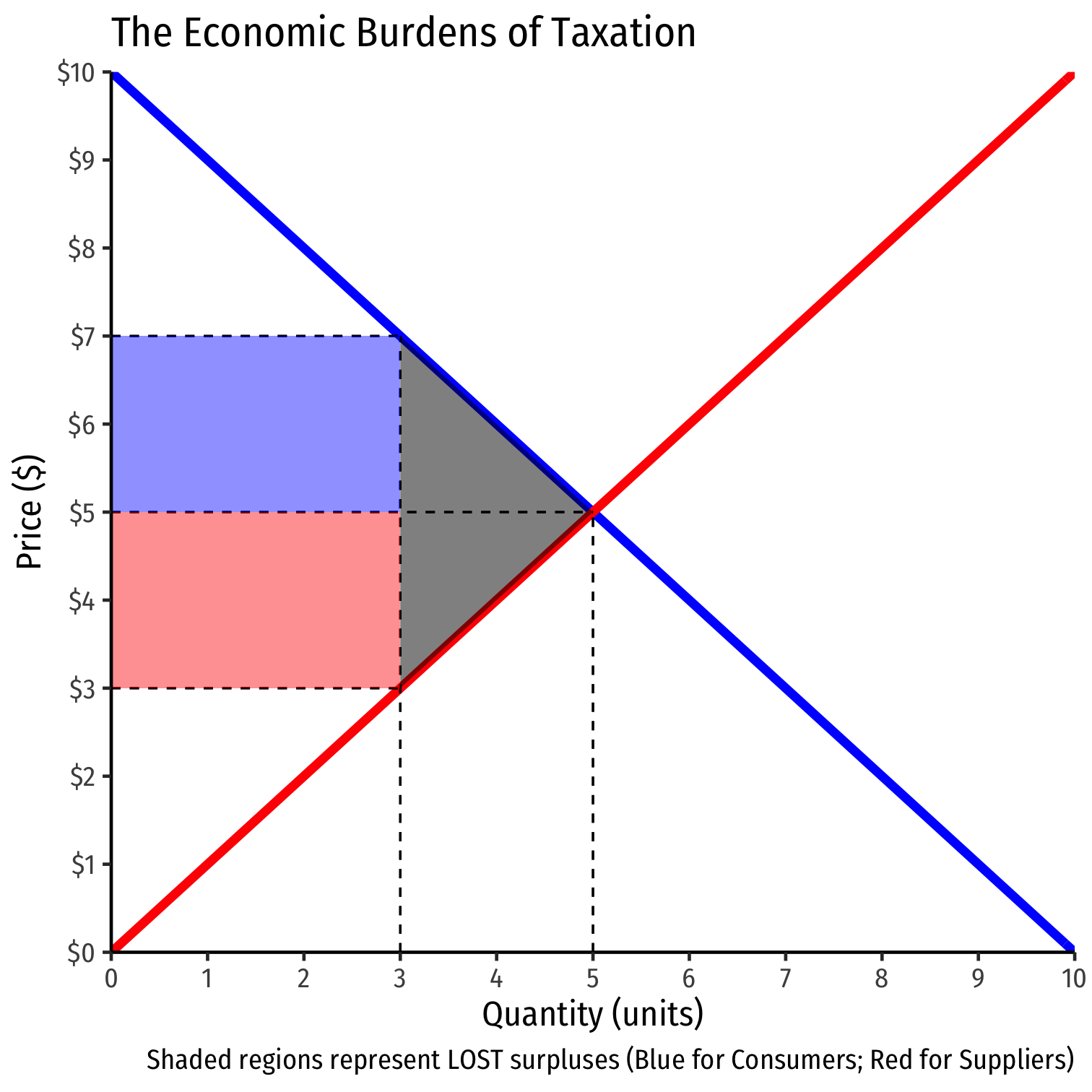

Recall from Micro: Economic Incidence of Taxation

Tax of t:

- G1=8

- DWL1=1

Tax of 2t:

- G2=12

- DWL1=4

Higher tax rates increase the rate of loss of surplus

- ΔG=1.5x increase

- ΔDWL=4x increase

In fact, ΔDWL=(Δt)2

Stationary Bandits: Overview

Stationary bandit monopolizes violence within own territory

- Purely selfish: protects ruler's ability to extract rents (taxes)

- Ruler has an "encompassing interest" over society

- Socially-beneficial side effect: reduces violence, (others!) theft, banditry; creates less uncertain tax payments; settles disputes and enforces property claims; encourages investment and exchange to expand surplus (to be regularly extracted)

Citizens may be exploited under stationary bandit, but preferable to roving bandits (anarchy)!

What Countries Are Stationary vs. Roving Bandits?

Do different States around the world (and over time) act more like roving bandits or stationary bandits?

What matters in determining this?

- turnover (violent or otherwise) frequency of leaders

- (un)certainty of succession

- risk of coup d'etats

- term limits?

Olson: Dictatorship vs. Democracy

Unlike dictator, democrats also participate in economy (alternative source of income)

Democrats have an "encompassing interest" in making sure the economy grows

Democracies require coalitions of interests to obtain a majority

Democracies tax and redistribute less income to ruling elites

Stable economic growth requires rule of law, secure property rights, etc. best achieved by democracies providing public goods

Limitations of Olson's Model

"The State" is modeled as a single agent (bandit in charge)

How do we get from "dictatorship" to "democracy?"

Assumes that stationary bandit has high state capacity

State Capacity

State Capacity

Might simply be defined as the State's ability to do things

In the simplest of early states, the stationary bandit just extracts taxes as ruling elite's revenues

Possibly to fund its armies

In more modern states, taxes used to provide public goods

So one strong shorthand for state capacity: ability to raise tax revenue

- But could most States even do this??

State (In)capacity and Tax Evasion I

- More of the world than you imagine is optimized for tax evasion

State (In)capacity and Tax Evasion I

- More of the world than you imagine is optimized for tax evasion

In Ukraine, an imported car is taxed heavily, so importers cut the cars in half (which are taxed lighter as ”spare parts” and then welded back together in the country))

State (In)capacity and Tax Evasion II

- More of the world than you imagine is optimized for tax evasion

In the Netherlands, houses were taxed based on their canal frontage (rather than height or depth), so they were built tall and thin (to minimize canal frontage)

99% Invisible: Vernacular Economics: How Building Codes & Taxes Shape Regional Architecture

State (In)capacity and Tax Evasion III

- More of the world than you imagine is optimized for tax evasion

In the UK, property taxes used to be based on the number of windows a building had, so many buildings still feature ”bricked up” window slots

99% Invisible: Vernacular Economics: How Building Codes & Taxes Shape Regional Architecture

State Capacity: Definitions from Literature

"State capacity can be thought of as comprising two components. First, a high capacity state must be able to enforce its rules across the entirety of the territory it claims to rule (legal capacity). Second, it has to be able to garner enough tax revenues from the economy to implement its policies (fiscal capacity). State capacity then should be distinguished from either the size or the scope of the state. A state with a bloated and inefficient public sector may be comparatively ineffective at implementing policies and raising tax revenues. Furthermore, historians agree that the eighteenth century British state had high state capacity even though it played a very limited role in the economy. Similarly, state capacity requires a degree of political and legal centralization, but it should not be identified with political centralization per se," (p.2).

Koyama, Mark and Noel D. Johnson, 2016, "States and Economic Growth: Capacity and Constraints," Explorations in Economic History, forthcoming

State Capacity as the Ability to Tax I

State Capacity as the Ability to Tax II

Koyama, Mark and Noel D. Johnson, 2016, "States and Economic Growth: Capacity and Constraints," Explorations in Economic History, forthcoming

Social Legibility I

Ruler confronts a massive knowledge problem

Before doing anything else (warfare, policies, public goods):

- what territory do you rule over?

- how many citizens do you rule over?

- how much wealth do they have?

- how can that wealth be extracted as taxes?

Social Legibility II

You might think you can just send your soldiers to count this all up and collect taxes

But:

- your people often speak different languages

- your people have different local customs

- your people have different weights and measures

- your people have different local landmarks, ways to navigate, and delineate things

- your people have overlapping property rights that they know how to navigate

- your people don't have systematized names

All of these things are impenetrable to an outsider

States can extract small fraction of taxes assessed

What States Want vs. What Society Is

Social "Legibility"

Bruges, Belgium, c.1500

Social "Legibility"

Bruges, Belgium, c.1500

Chicago, U.S., c.1900

Social "Illegibility" I

James C. Scott

1936-

"How were the agents of the state to begin measuring and codifying, throughout each region of an entire kingdom, its population, their land

holdings, their harvests, their wealth, the volume of commerce, and so on? The obstacles in the path of even the most rudimentary knowledge of these matters were enormous. The struggle to establish uniform weights and measures and to carry out a cadastral mapping of landholdings can serve as diagnostic examples. Each required a large, costly, long-term campaign against determined resistance. Resistance came not only from the general population but also from local powerholders; they were frequently able to take advantage of the administrative incoherence."

Scott, James C, (1999), Seeing Like a State

Social "Illegibility" II

James C. Scott

1936-

Each undertaking also exemplified a pattern of relations between local knowledge and practices on one hand and state administrative routines on the other, a pattern that will find echoes throughout this book. In each case, local practices of measurement and landholding were "illegible" to the state in their raw form. They exhibited a diversity and intricacy that reflected a great variety of purely local, not state, interests. That is to say, they could not be assimilated into an administrative grid without being either transformed or reduced to a convenient, if partly fictional, shorthand.

Scott, James C, (1999), Seeing Like a State

Social "Illegibility" III

James C. Scott

1936-

Obliged to grope its way on the basis of sketchy information, rumor, and self-interested local reports, the state often responded belatedly and inappropriately. Equity in taxation, another sensitive political issue, was beyond the reach of a state that found it difficult to know the basic comparative facts about harvests and prices. A vigorous effort to collect taxes, to requisition for military garrisons, to relieve urban shortages, or any number of other measures might, given the crudeness of state intelligence, actually provoke a political crisis. Even when it did not jeopardize state security, the Babel of measurement produced gross inefficiencies and a pattern of either undershooting or overshooting fiscal targets. No effective central monitoring or controlled comparisons were possible without standard, fixed units of measurement.

Scott, James C, (1999), Seeing Like a State

Even "Last Names" Don't Exist!

James C. Scott

1936-

Only wealthy aristocrats tended to have fixed surnames…Imagine the dilemma of a tithe or capitation-tax collector [in England] faced with a male population, 90% of whom bore just six Christian names (John, William, Thomas, Robert, Richard, and Henry).

Scott, James C, (1999), Seeing Like a State

The Variation in Local Weights and Measures I

James C. Scott

1936-

Most early measures were human in scale. One sees this logic at work in such surviving expressions as a "stone's throw" or "within ear

shot" for distances and a "cartload," a "basketful," or a "handful" for volume. Given that the size of a cart or basket might vary from place to place and that a stone's throw might not be precisely uniform from person to person, these units of measurement varied geographically and temporally. Because local standards of measurement were tied to practical needs, because they reflected particular cropping patterns and agricultural technology, because they varied with climate and ecology, because they were "an attribute of power and an instrument of asserting class privilege," and because they were "at the center of bitter class struggle," they represented a mind-boggling problem for statecraft.

Scott, James C, (1999), Seeing Like a State

The Variation in Local Weights and Measures II

James C. Scott

1936-

The pint in eighteenth-century Paris was equivalent to 0.93 liters, whereas in Seine-en-Montane it was 1.99 liters and in Precy-sous-Thil, an astounding 3.33 liters. The aune, a measure of length used for cloth, varied depending on the material (the unit for silk, for instance, was smaller than that for linen) and across France there were at least seventeen different aunes.

Scott, James C, (1999), Seeing Like a State

The Political Economy of Local Weights and Measures I

James C. Scott

1936-

Virtually everywhere in early modern Europe were endless micropolitics about how baskets might be adjusted through wear, bulging, tricks of weaving, moisture, the thickness of the rim, and so on. In some areas the local standards for the bushel and other units of measurement were kept in metallic form and placed in the care of a trusted official or else literally carved into the stone of a church or the town hall. Nor did it end there. How the grain was to be poured (from shoulder height, which packed it somewhat, or from waist height?), how damp it could be, whether the container could be shaken down, and finally, if and how it was to be leveled off when full were subjects of long and bitter controversy.

Scott, James C, (1999), Seeing Like a State

The Political Economy of Local Weights and Measures II

James C. Scott

1936-

A good part of the politics of measurement sprang from what a contemporary economist might call the "stickiness" of feudal rents. Noble and clerical claimants often found it difficult to increase feudal dues directly; the levels set for various charges were the result of long struggle, and even a small increase above the customary level was viewed as a threatening breach of tradition. Adjusting the measure, however, represented a roundabout way of achieving the same end.

The Political Economy of Local Weights and Measures III

James C. Scott

1936-

The local lord might, for example, lend grain to peasants in smaller baskets and insist on repayment in larger baskets. He might surreptitiously or even boldly enlarge the size of the grain sacks accepted for milling (a monopoly of the domain lord) and reduce the size of the sacks used for measuring out flour; he might also collect feudal dues in larger baskets and pay wages in kind in smaller baskets. While the formal custom governing feudal dues and wages would thus remain intact (requiring, for example, the same number of sacks of wheat from the harvest of a given holding), the actual transaction might increasingly favor the lord. The results of such fiddling were far from trivial. Kula estimates that the size of the bushel (boisseau) used to collect the main feudal rent (taille) increased by one-third between 1674 and 1716 as part of what was called the reaction feodale.

Scott, James C, (1999), Seeing Like a State

The Political Economy of Taxation I

James C. Scott

1936-

"Absolutist France in the seventeenth century is a case in point. Indirect taxes-excise levies on salt and tobacco, tolls, license fees, and the sale of offices and titles-were favored forms of taxation; they were easy to administer and required little or nothing in the way of information about landholding and income. The tax-exempt status of the nobility and clergy meant that a good deal of the landed property was not taxed at all, transferring much of the burden to wealthy commoner farmers and the peasantry. Common land, although it was a vitally important subsistence resource for the rural poor, yielded no revenue either."

The Political Economy of Taxation II

James C. Scott

1936-

What must strike any observer of absolutist taxation is how wildly variable and unsystematic it was...[T]he main direct land tax, the taille, was frequently not paid at all and that no community paid more than one-third of what they were assessed. The result was that the state routinely relied on exceptional measures to overcome shortfalls in revenue or to pay for new expenses, particularly military campaigns. The crown exacted "forced loans" (rentes, droits alienes) in return for annuities that it might or might not honor; it sold offices and titles (venalites d'of/ices); it levied exceptional hearth taxes (foua ges extraordinaires); and, worst of all, it billeted troops directly in communities, often ruining the towns in the process.

Takeaways

Taxation is extremely irregular, uncertain, and profoundly unequal

States struggle to collect any significant tax revenue

States cannot project power beyond their capital, military garrisons

Sharp class divisions between ruling elites and serfs

Local communities and customs trump all other concerns - there is no "nation" or "country"

- Nationalism is a 19^th^ century invention!